Shrewdly reimagining H.G. Wells’ 1897 “Grotesque Romance” for a contemporary audience, writer-director Leigh Whannell’s 2020 take on The Invisible Man seemed to break the curse that had afflicted Universal Pictures’ flop-sweaty efforts to alchemize box-office gold from its roster of classic movie monsters. (Remember The Mummy? No, the other one. No, the Tom Cruise one.) Besides flexing the gruesomely satisfying action chops the filmmaker debuted in his 2018 sci-fi actioner Upgrade, Whannell’s feature effected a crucial alteration to Wells’ durable premise by shifting the story’s perspective from the titular villain to his primary victim. By envisioning the Invisible Man as the worst version of every abusive, obsessive ex-boyfriend, Whannell created an unlikely and shockingly effective hybrid of a 1990s-style stalker thriller and a contemporary sci-fi horror picture.

His latest directorial project returns to the “Universal monster on an indie budget” well with a reboot/reinterpretation of Curt Siodmak’s iconic 1941 chiller The Wolf Man. Horror aficionados could be forgiven for being a bit apprehensive, given that werewolf movies have long been a somewhat dodgy subgenre, quality-wise, no matter who is behind the camera. The 21st century has given us only two truly great “straight” entries, Dog Soldiers and Ginger Snaps, both made more than two decades ago. Meanwhile, Joe Johnston’s 2010 attempt at a period Gothic remake of Siodmak’s feature has been entirely forgotten, perhaps a bit unjustly. (The Danny Elfman score slaps, at least.) However, given that Whannell managed to make Universal’s least overtly scary villain into the stuff of PTSD-fueled nightmares, perhaps the studio thought that he was the director to make a hairy, carnivorous brute in ragged trousers a bit less goofy.

Alas, Wolf Man is not a particularly good horror movie, although its problems have less to do with the lycanthropic premise itself than the difficulty that Whannell and co-writer Corbett Tuck exhibit in finding a consistent, emotionally authentic approach to the material. Instead of the so-simple-it’s-brilliant elevator pitch of The Invisible Man – What if your creepy, controlling ex could invade and upend your life with impunity? – Whannell’s latest presents a smorgasbord of half-baked, conflicting metaphors, none of which are well supported by the clunky screenplay. It’s a disappointing step backward for the filmmaker, not the least because Wolf Man does have its moments. Set primarily in the Oregon Cascades (played by New Zealand’s criminally scenic Southern Alps) and suffused with a fitting atmosphere of misty, primeval desolation, the feature introduces some legitimately invigorating choices to the subgenre through its visual and sound design. Unfortunately, these aren’t enough to make up for the film’s hamfisted script, limp characterization, and general hesitancy in committing to and elaborating on a single, coherent theme.

Things start promisingly enough: In 1995, as a young boy named Blake (Zac Chandler) dwells with his single father (Ben Prendergast) in a remote mountain valley in west-central Oregon. A twitchy ex-Marine whose severe, domineering demeanor betrays his fearful stance toward a world he sees as fundamentally cruel and violent, Blake’s father placed a rifle into his son’s hands as soon as the boy could walk. (In a film that is otherwise allergic to understatement, the screenplay’s deafening silence regarding Blake’s absent mother is a welcome touch; it’s easy to discern how Dad’s rigid parenting approach might trace back to his spouse’s sudden death.) While hunting one day in the dense coniferous forests that surround their farm, father and son have a frightening encounter with an aggressive creature that may or may not be the deranged hiker that vanished in the range sometime back. Blake doesn’t get a clear look at this animal from the vantage of their deer stand, but the incident appears to profoundly rattle his already-paranoid dad.

Thirty years later, Blake (Christopher Abbott) is living in San Francisco, a between-projects writer currently serving as a stay-at-home dad to his young daughter, Ginger (Matilda Firth). The two have a close, warmhearted bond, although Blake is apprehensive about his protectiveness slipping into panicky browbeating, given that this behavior from his own father is ultimately what drove him from the rugged Cascades to the big city. Blake’s wife, Charlotte (Julia Garner), is the breadwinner of the family, a career-minded journalist who is slightly envious of the relationship between her husband and daughter, but also sufficiently self-aware to admit to Blake (and herself) that motherhood has always felt like an awkward fit. Into this photogenic but shaky family unit drops a token from the past: keys to Blake’s childhood home, delivered alongside a notice that his long-missing father has been declared legally dead. Blake proposes that the three of them relocate to Oregon for the summer, ostensibly to clear out the farmhouse but also to settle accounts with the phantoms he’s never quite managed to outrun.

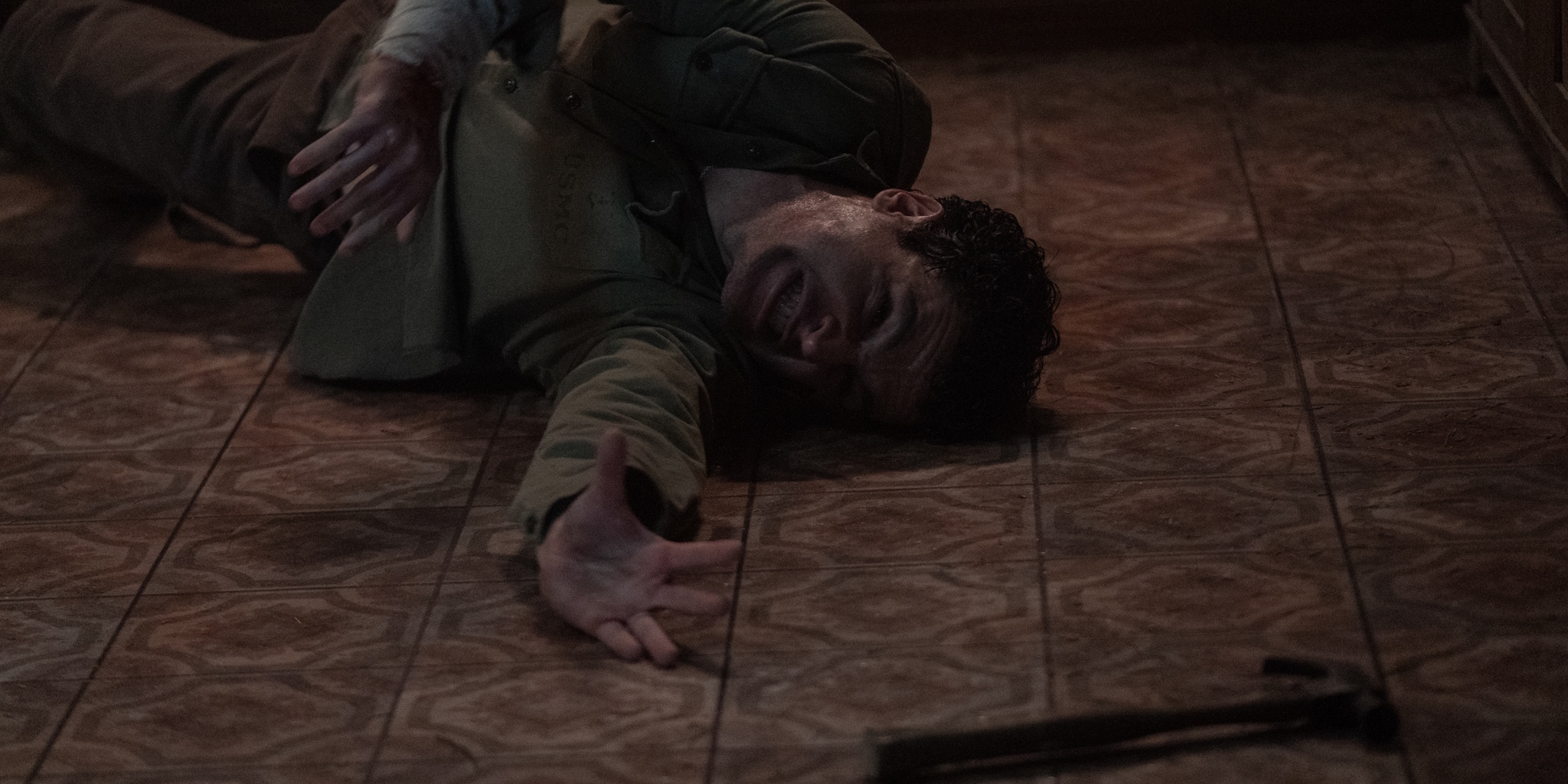

Unfortunately, a calamity befalls the family before they even reach the site of Blake’s formative traumas. (Wolf Man is somehow both ruthlessly efficient and strangely sluggish.) While struggling to find the winding, unpaved track to his dad’s old place in the twilight gloom of the forest, Blake swerves to avoid a man-like shape in the road, sending the family’s moving van careening into a nearby thicket of trees. Charlotte and Ginger are unharmed, but a howling, mostly unseen beast mauls Blake’s arm in the aftermath. The three are forced to make a run for the nearby farmhouse, teeing up the scenario that defines the rest of the film: a long, dark night in which the besieged family is terrorized by a prowling, bloodthirsty creature. It turns out, however, that there is already a nascent monster inside the house. Blake’s infected injury begins to transform his flesh and his mind, stripping away his humanity with frightening speed.

To its credit, Wolf Man approaches its titular monster in a relatively novel manner. Discarding the occult baggage of lunar cycles, silver bullets, and Romani curses, Whannell’s feature nicks a page from David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986), imagining lycanthropy as gnarly-ass infection that warps its host into a repulsive, feral hybrid of man and beast. Blake’s teeth and hair begin falling out, replaced by new versions befitting a predator, while muscles and tendons rearrange themselves beneath his increasingly clammy, pockmarked skin. The film’s creature design hews to “hirsute guy with fangs” look consistent with the original The Wolf Man and its kin, such as Werewolf of London (1935) and I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957). However, Blake’s appearance is more distressing than fearsome. By design, it doesn’t seem like a cool, super-powered transformation: It looks like we are watching someone succumb to a degenerative disease.

Even more disturbing than his physical mutation, however, is Blake’s rapid mental devolution. The film vividly employs digital effects to illustrate its doomed protagonist’s heightening senses: A crawling spider sounds like a bull rampaging through a china shop to his canine hearing, while his newly sensitive eyes see the nocturnal forest as a cacophonous, phosphorescent wonderland straight out of Pandora. Yet Whannell presents these enhancements more as incidental side effects than as legitimate tradeoffs for the character’s eroding humanity. Indeed, the film forces viewers to watch helplessly as Blake drifts further and further into a sensory netherworld that isolates him from his wife and daughter. Soon his ability to both speak and comprehend language slips away, as Charlotte and Ginger begin to resemble creepy, doll-like creatures whose garbled speech he cannot understand and whose blank expressions he can no longer read. This disintegration of human communication is perhaps the film’s most effective horror flourish, recalling Wes Craven’s harrowing episode “Wordplay” from the 1985 revival of The Twilight Zone.

In most other respects, Wolf Man is, at best, a serviceable creature feature. It’s suitably atmospheric, but it never figures out how to shed the inherent silliness of a growling guy in prosthetics running around on all fours. (No less a figure than Mike Nichols likewise failed to stick the landing in his revisionist 1994 take on the subgenre, Wolf.) Granted, there is an appealing simplicity to the film’s stripped-down approach to the werewolf myth – compressing the horror that another feature might have drawn out over months into the events of one night – but Whannell’s restlessness is evident in the aimless mechanics of the plot on a minute-to-minute basis. Instead of hunkering down in one spot until dawn, the family keeps rushing around in a panic, sometimes for no logical reason beyond the filmmaker’s apparent interest in changing up a sequence’s spatial geography

More irritatingly, Wolf Man’s characterization is far too thin to support the emotional heft that the screenplay is plainly striving to achieve. The script at once feels heavy-handed and malnourished, clumsily declaring what it lacks the patience to establish through more measured means. The viewer simply doesn’t spend enough time with this faintly sketched family unit for the horror of its sudden and rapid disintegration to hit especially hard. The film’s lead actors are usually compelling performers: Abbott (James White, Possessor) is maturing into one of American indie cinema’s low-key great leading men, and the three-time Emmy-winning Garner (Ozark, The Assistant) basically had nothing left to prove by the time she turned 30. However, Wolf Man’s hamfisted dialogue is doing neither actor any favors, particularly Garner, who has never sounded less convincing than when her character awkwardly stammers lines like, “You’re my best friend,” to a man who seems less like her husband and more like a co-worker she sort of knows. The film is also maddeningly inconsistent in its treatment of Charlotte, who is either a terminally soft City Girl or a badass survivor, depending on the momentary needs of the scene.

Most of the blame for Wolf Man’s failings is attributable to its stumbling screenplay, and perhaps to a storied production history in which the film’s shape kept shifting. (At one point, the muse-director pairing of Ryan Gosling and Derek Cianfrance was attached to the project. What might that have looked like?) Certainly, Whannell and Tuck have trouble deciding which metaphorical lens to apply to their version of the werewolf legend. Is this a film about the generational cycle of emotional violence perpetrated by overprotective parents? Or is it about the Jekyll-and-Hyde mutation of a benevolent protector into a hotheaded abuser? Or the cruelty of disease eroding our loved ones before our eyes? Wolf Man gestures limply toward all these readings, but it doesn’t truly support any of them, preferring to rely on crude, low-impact manipulation of the audience’s sympathy. (See? The little girl is sad that her daddy is sick. Ergo, we are sad.) This vagueness proves to be the film’s soft, vulnerable underbelly, a fatal flaw in a subgenre that is theoretically about the inherent savagery of humanity.

Wolf Man opens in theaters everywhere on Friday, Jan. 17.