Many horror movies aspire to a general impression of nightmarishness, but it’s an uncommon film that aims to re-create, as closely as possible, the uncanny anti-logic of dreams. One reason that this feat is so rarely attempted is obvious: Nightmares might haunt our waking hours with their terrifying imagery and harrowing sensations, but they usually make for lousy stories. Who wants to sit through a muddled sequence of nonsensical, loosely connected vignettes that barely make sense to the dreamer? David Lynch is probably the most acclaimed filmmaker to decisively crack this problem, presenting oneiric cinematic visions that don’t make a hell of a lot of sense as traditional narratives but nonetheless feel compelling in some ineffable, atavistic way.

Writer-director Kyle Edward Ball has pulled off a comparable feat with his debut feature, Skinamarink, an experimental horror feature that strives to replicate the feeling of a nightmare – specifically, a childhood nightmare. Ball’s film captures, to deeply unsettling effect, the primordial immensity that dreams can attain during that fleeting period when we still see the waking world as a mysterious, terrifying place. However, what sets Skinamarink apart from so many micro-budget horror features is not just its unnervingly precise impact or its strikingly avant-garde presentation, but its nimble reckoning with the inextricable entanglement of dreams and audiovisual media in modern life. It is one of the few horror features – and certainly the most mesmerizing – to unflinchingly explore the outer limits of the videographic image since Lynch’s own Inland Empire (2006). Indeed, Ball might be the first post-YouTube, post-r/NoSleep filmmaker to approach the veteran director’s intuitive grasp of dreamscapes. Jane Schoenbrun’s 2021 cult sensation We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021) was birthed by similar Internet spaces, but Ball’s film is operating on an entirely different level. (Schoenbrun, to their credit, was instrumental in bringing early attention to Skinamarink.)

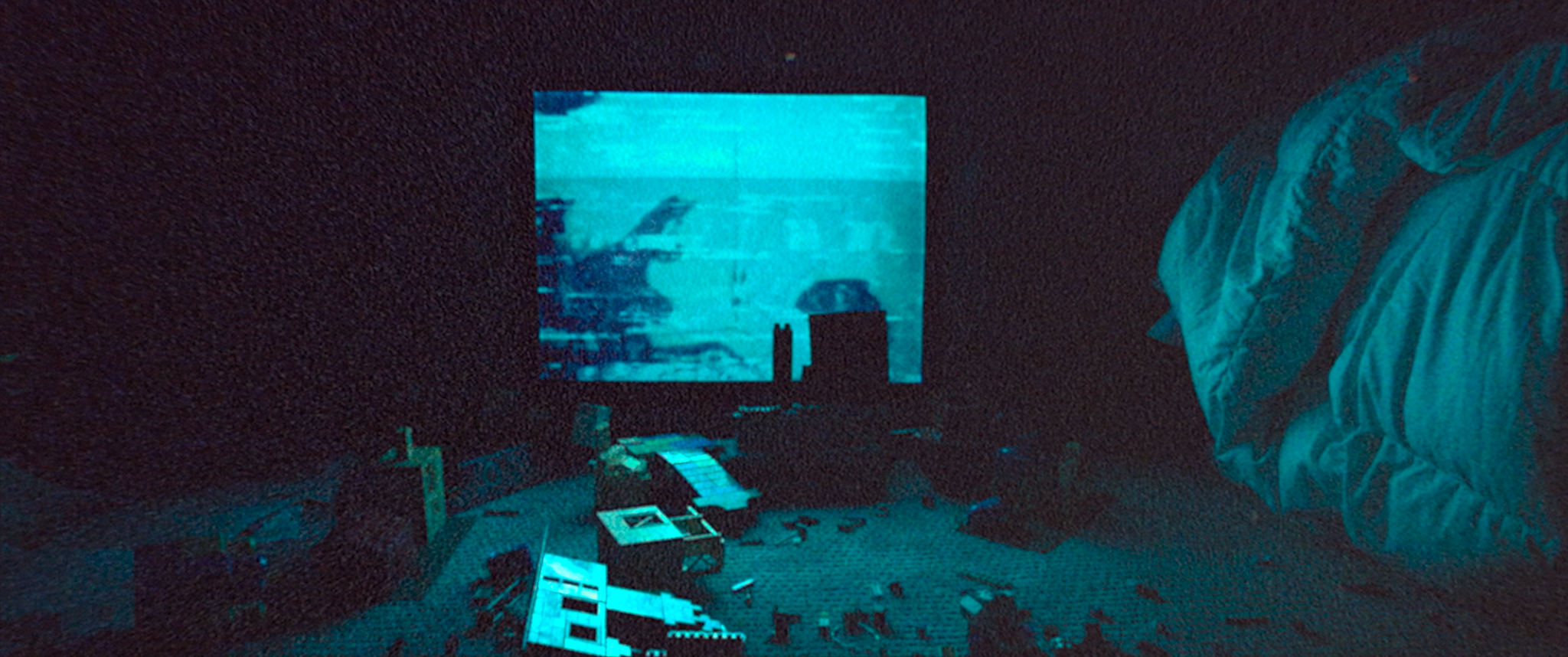

Theme and form attain a stunning, self-reflexive union in Ball’s feature, which shows us not just a nightmare in cinematic form, but a study of the complex yet primal dynamic between light, darkness, and fear. In an era when a rabbit hole of endless creepypasta terror is only a smartphone tap away, Skinamarink is a formidable reminder that all horror filmmaking is shadow play at heart, a danse macabre between the seen and the unseen. Ball’s feature is fittingly absorbed with light as a physical phenomenon that reveals and deceives. It conveys a hypnotic fascination with the blazing filament of an incandescent light, the flickering phosphors on a CRT television, and the phantom maggots that squirm in the grainy murk of a recorded image. It’s hardly incidental that Skinamarink features a surreal, nauseatingly tense variation on the look-under-the-bed trope: The human compulsion to peer into the shadows is forever struggling with our terror at what might be staring back at us.

Despite its experimental trappings, Skinamarink unquestionably has a story, but it presents that story in such a slippery and fragmented way that it is difficult to state with confidence what precisely “happens.” Here is what seems reasonably certain: It is 1995, and two young children, older sister Kaylee (Dali Rose Tetreault) and little brother Kevin (Lucas Paul), are living in a drab suburban house with their frequently absent father (Ross Paul). Mom is no longer in the picture, but what exactly fractured this family is left ambiguous. At some point Dad leaves and does not return, a distressing turn of events that roughly coincides with a perplexing mutation: The house’s doors and windows seem to vanish, entrapping Kaylee and Kevin in a drywall limbo devoid of fresh air or natural light.

The children adapt as well as they can to this new reality, sustaining themselves on dry cereal and building a blanket fort around the soothing flicker of the living-room television. Then the whispering starts, a creepy, indistinct croak that beckons first Kaylee and then Kevin into the dark, yawning gloom that now suffuses the house’s once-familiar nooks and crannies. The world begins to turn upside-down and sideways, and soon the house’s fixtures and furniture begin slipping away, as if carted off by Yōko Ogawa’s Memory Police. The house has become not a prison, but a chasm – an abyss that is crumbling ominously at the edges, gaping wider and wider like a hungry mouth.

In the loosest sense, Skinamarink relies on the well-worn, escalating structure of a haunted-house tale: eerie, mysterious events begin occurring and then gradually intensify into a terrifying, violent crescendo. This might be the only conventional aspect of Ball’s film, but it is perhaps a necessary one, a rare landmark of genre familiarity in what is otherwise an oblique, alienating landscape. Literally oblique, as it happens: Ball and cinematographer Jamie McRae employ a mise-en-scène that can only be described as counterintuitive, relying on unexpected framing that obscures as much of the action as it reveals. They fill their feature with low-angle shots of bare walls and ceilings, extreme close-ups of objects and surfaces, and point-of-view footage in which the camera seems to move just a little too sluggishly. Skinamarink rarely gives the audience a clear view of anything, even its young protagonists; Kaylee and Kevin are often glimpsed only as socked feet that creep anxiously past Ball’s ankle-level camera.

Shinamarink is not a found-footage feature, but this disaffecting approach to composition – combined with purposefully underlit spaces and the faux-analog grain added to the film’s digital footage in post-production – lends it a novel sensation of frustrated voyeurism. This is the film teaching the viewer how to watch it, as the phrase goes, accustoming them to the constraints (if not the treachery) of images. One can only see that which is illuminated, a truth that feels increasingly salient to both characters and audience as they squint into the house’s featureless murk, searching for the minute shift in contrast that might reveal a looming, ravenous threat. In this, Ball’s film rather unexpectedly recalls Nope (2022), Jordan Peele’s recent treatise on – among many things – the limitations of the eye, both biological and mechanical. Whereas Peele’s feature relied on Hoyte Van Hoytema’s massive, day-for-night photography to play with the physics (and psychology) of visibility, Skinamarink shrinks its viewing window down to a maddeningly fuzzy standard-def postage stamp. Both films elicit the same skin-crawling question, however: What the hell am I looking at?

Like all nightmares, Skinamarink invites manifold interpretations, even if no single reading is completely satisfying. Turn it one way and one can make out the vague but horrific outline of an abusive childhood; turn it another and one can perceive a memory palace of liminal anxieties at the sunset of the analog era. Ball shares Lynch’s fascination with the corruption of domestic spaces and with the notion that monsters can (and often do) lurk in the most ordinary surroundings. The significant demographic of Gen Xers and Millennials who hail from broken homes will doubtlessly resonate with the rotten undertones in Ball’s aggressively banal setting. Long-dormant sensations of traumatic upheaval, crushing guilt, and latchkey loneliness will come bubbling up as Kaylee and Kevin fearfully wander a house that is no longer a home, but instead a lair that belongs to some terrifying Other.

At least the television remains: that reliable, eternally glowing friend to the Nickelodeon cohort. In Poltergeist (1982), the TV set was portrayed as a sinister trap door enshrined (ironically) smack in the middle of the living room. The new Sony Trinitron became a Morlock hole, a tunnel that allowed the unquiet dead to scuttle unseen into American suburbia – much as the smiling cruelty of Reaganism slithered its way into the hearts of ex-hippie Boomers like the Freelings. A generation-and-a-half later, Ball flips this Luddite sentiment on its head, presenting the television set as the campfire that keeps the creatures of the night at bay. (Here he differs sharply from Lynch, who often depicts electricity as an unnatural conduit for evil.) Even a well-tended flame may gutter and fade eventually, however. When it does, the yellow-eyed monsters that circle just beyond the light’s reach will finally close in for the kill.

Skinamarink is now playing in select theaters and is available to stream on Shudder.