[Originally published at Cinema St. Louis’ The Lens.]

History is littered with firsts that aren’t actually firsts. Whenever a self-appointed expert blithely asserts that “so-and-so was the first person to do such-and-such,” it’s probably a safe bet that there was, in fact, someone who pulled off the feat in question even earlier. (Odds are also pretty good that this forgotten pioneer was not a White man; hence the tendency to brush aside their achievements.) For example, everyone knows that the first feature-length animated movie was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Except it wasn’t: There were earlier features created by Argentine animator Guirino Cristiani – now lost, unfortunately. And as for the oldest surviving animated feature, that honor goes to the stop-motion fairy tale The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926), written, directed, and animated by German filmmaker Lotte Reiniger.

The Haywood family legacy is built on a similar forgotten first. The Black jockey riding a galloping horse in one of Eadweard Muybridge’s revolutionary 19th-century photographic sequences was the great-great-great-grandfather of Hollywood horse trainers OJ (Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald (Keke Palmer). As OJ unsuccessfully attempts to explain to the dubious cast and crew of a commercial shoot – obliging the more extroverted Emerald to jump in and pick up the slack – this makes Grandpa Haywood cinema’s first horse trainer, stuntman, and movie star, all rolled into one. (Ironically, the real-world truth is a bit more complicated.)

The Haywoods end up getting fired from the commercial shoot when the crew’s unwillingness to heed OJ’s safety protocols leads to a near-miss incident with their horse, Lucky. Such setbacks have unfortunately been typical of the past six months, ever since the accidental death of their father, Otis Sr. (Keith David). The manner of the elder Haywood’s demise was equal parts senseless and inexplicable: a mini-meteor storm of small, seemingly random metal and plastic objects struck their ranch one afternoon, fatally lodging a quarter in Dad’s skull.

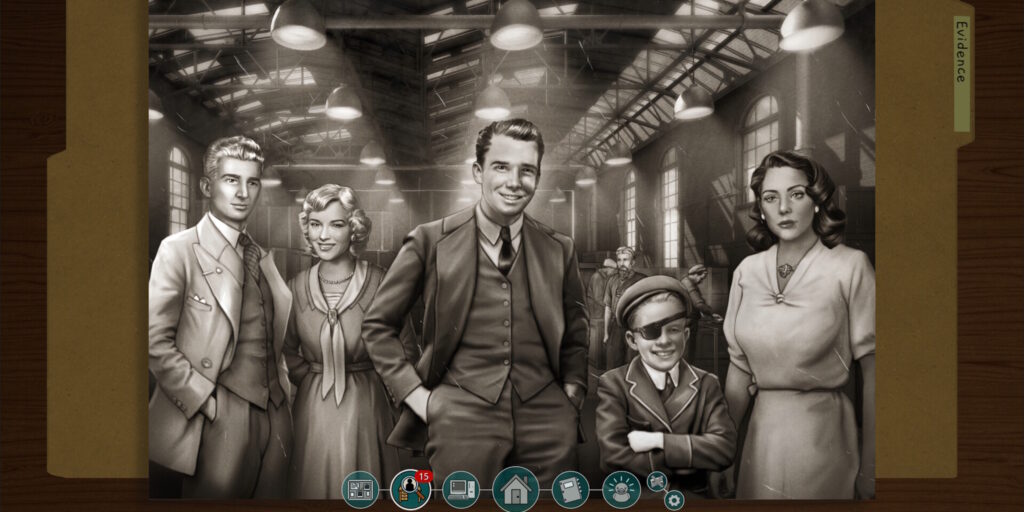

Despite his sensible, hard-working attitude, OJ has been struggling ever since to keep the family business afloat. He has received little substantive support from Emerald, an ambitious, natural-born hustler who has a half-dozen different side projects going at any given time – Actor! Singer! Motorcycle stuntwoman! – but is nonetheless semi-allergic to hard work. Faced with mounting bills, OJ has been selling off the ranch’s horses one by one to Ricky “Jupe” Park (Steven Yeun), a former child star who now owns a tacky Western theme park and stunt show just down the road. OJ insists that he will buy the animals back once the ranch is on its feet again, but it’s unclear whether he actually believes this bit of self-delusion. The Haywood legacy seems to be circling the drain.

As it happens, the day that OJ sells Lucky to Jupe proves to be a fateful one, albeit for unexpected reasons. That night, while retrieving a horse that has mysteriously slipped out of the ranch’s stable, OJ sees … something. Something big. It darts through the low clouds and behind the steep, scrubby hills that surround the ranch’s gulch. Whatever “it” is, electrical power shuts down when it hovers directly overhead, and as everybody knows, such localized blackouts are a classic sign of otherworldly visitors. (Or so midcentury ufology cranks – and, by extension, Close Encounters of the Third Kind – have long insisted.) The encounter spooks OJ, but Emerald smells opportunity. In short order, they rope a hapless Fry’s Electronics technician, Angel (Brandon Perea), into their scheme to capture the granddaddy of all UFO videos, an “Oprah shot” that will provide incontrovertible proof of alien life – and put the Haywood name back on the map with another historic first.

The jittery urgency of the Haywoods’ documentary ambitions – and the gnawing certainty that it’s only a matter of time until TMZ shows up to snatch away the dollars and the glory – conveys writer-director Jordan Peele’s interest in our collective addiction to the Oprah shot, even when the images in question are horrific. The kids who watched the Twin Towers fall eternally on a loop are, after all, now old enough to have families and mortgages (or they would, if anyone could afford a mortgage nowadays). Peele’s highly anticipated third feature is, in part, a story about the irresistible compulsion to watch the world burn through the distancing porthole of the photographic frame. Or, better yet, to hold the copyright on the first apocalyptic images to go viral.

Nope is, in fact, about a lot of things, and the most conspicuous criticism that one might level at Peele’s film is that it is somewhat overstuffed, a whirlwind of themes that trail off into wispy nothing as often as they coalesce into a resonant whole. Like Us (2019), the director’s latest feature is brimming with ideas, although here Peele has discarded quasi-surreal allegory for a more grounded story of enterprising hustle and sibling solidarity. Or, at least, as grounded as things can be in a sci-fi horror flick that owes as much to Predator (1987) and Under the Skin (2013) as it does to Close Encounters.

Indeed, the aspect of Nope that most distinguishes it from Peele’s prior films is its unabashed reveling in Black pride and excellence. The Haywoods are very good at what they do, and the film has some nifty payoffs in its final stretch that rely on the audience’s low-key underestimation of both OJ and Emerald. Of course, Peele, ever the canny commentator, doesn’t completely shy away from acidic sociopolitical subtext. Early scenes of OJ’s awkward on-set experience astutely zero in on the way that Black people can be simultaneously scrutinized and ignored in White-dominated professional spaces.

As noted, however, Nope is juggling a multitude of notional balls: the unholy power of an entertaining spectacle, the short-sighted folly of monetization, and humankind’s uneasy detente with nature, to name a few. The film is uneven in its engagement with these themes, and although Peele seems to regard all of them with sincerity, some inevitably end up feeling a bit orphaned. For one, the contemporary urge to document every waking moment of our lives is stretched to its absurdist end point, but it never pays dividends beyond the shallow, implied reproach that we should put down our smartphones and experience life instead of recording it.

The screenplay might be notably shaggy when compared to the laser-cut precision of Get Out (2017), but Nope’s moment-to-moment formal choices are often downright stunning. Some of editor Nicholas Monsour’s cuts are museum-worthy in their breathless virtuosity, flicking away from scenes in a manner that both conceals and reveals. The film also benefits mightily from the presence of the great cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema, whose credits include Her (2013), Ad Astra (2019), and all of Christopher Nolan’s post-Batman features. He transforms Nope into Peele’s best-looking feature to date, particularly in its luminous, slate-blue night sequences. The murk that occasionally obscured the action in Us is here elevated from a bug to a feature, with nocturnal imagery that shivers right at the edge of distinguishability, amplifying the characters’ (and the viewer’s) prickly uncertainty about what exactly they are looking at.

Peele gives the film an unconventional, slightly arrhythmic structure by leaning hard into a seemingly tangential flashback subplot about Jupe’s short-lived 1990s sitcom, Gordy’s Home. This series about a suburb-dwelling chimpanzee ended in spectacular, gruesome tragedy when one of the ape stars went berserk during a live taping, an incident that Peele bestows with a whiff of urban-legend spookiness. What this has to do with Nope’s primary plot is not immediately apparent, but Jupe’s nervously amused recollection of that terrible day provides a clue. When recounting the story to Emerald, he does so via an early-2000s Saturday Night Live sketch about the event, rather than revisiting the horrific reality he actually lived. (Yeun’s Barnum-esque small-time showman never seems like a bigger bullshitter than when he’s marveling appreciatively at Chris Kattan’s comedic chops.)

Yeun’s facility for nakedly mingling Jupe’s cheerful enthusiasm and unburied trauma is key to selling a character whose pitiable history doesn’t quite outweigh his mercenary disregard for good taste (or lethal danger). Pitch-perfect casting has always been one of Peele’s strong suits, as further evidenced by the great, gravel-voiced Michael Wincott (The Crow, Alien: Resurrection), who makes an early appearance as an acerbic cinematographer and then later rejoins the story in the third act. Ultimately, however, the film rests on Kaluuya and Palmer, who strike such a charming, credible bond you would swear they are real-life siblings. Palmer is all unbridled, infectious energy, while Kaluuya gets to play a bit against type as a reserved workaholic who mutters every line into his chest and struggles to relate to anything without four legs. Together, they comprise the yin-and-yang heart of Nope, presenting the sort of winning, realistic portrait of Black aplomb, ingenuity, and endurance that is rarely sighted in contemporary Hollywood genre cinema.

Nope opens in theaters everywhere on Friday, July 22.