Something terrifying and unfathomable stalks the world in Longlegs. For decades, a mysterious serial killer has been creeping into quiet, middle-class homes in the Pacific Northwest. Like a spider crouching in a cobwebby corner, he oversees a recurring sacrament of evil, as seemingly well-adjusted, church-going fathers annihilate their families and then themselves. The interloper never seems to participate directly in this bloody business, but he claims it as his handiwork in the coded letters he leaves behind, signing each with his nom de guerre: Longlegs.

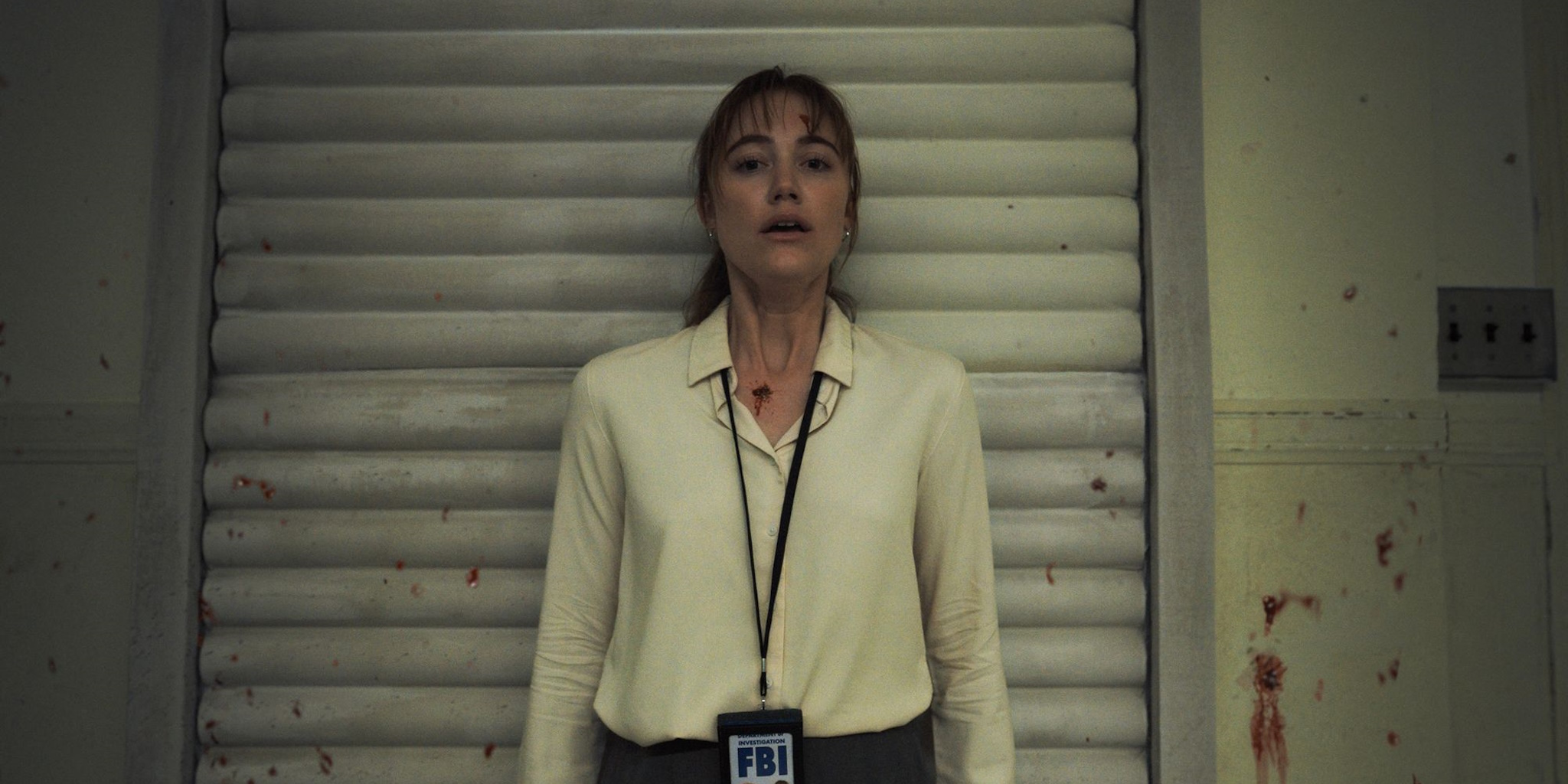

This case has stagnated for years – no clues, no motive, no leads – but it suddenly quivers to life when FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) is assigned to the investigation. Lee is relatively green, but her out-of-the-blue hunch during a recent case is sufficient to bring her uncanny faculties to the attention of her boss, agent Carter (Blair Underwood). Granted, Lee only answers about half the questions correctly during a peculiar clinical evaluation intended to assess her clairvoyant abilities. “Half psychic is better than no psychic,” mutters Carter pragmatically, seeing only a tool for a task. Lee, however, is both fascinated and repelled on primal level by the Longlegs case, which wriggles into her mind and exhumes long-buried fears.

It’s a familiar template: a young but resolute female investigator relentlessly pursues a slippery serial killer. The comparisons to The Silence of the Lambs feel inevitable – if only because Jonathan Demme’s 1991 feature perfected the form – although the added semi-clairvoyant twist recalls psychic horror-thrillers such as The Fury (1978) and The Dead Zone (1983). However, writer-director Osgood Perkins has crafted something far more unnerving than a crime thriller about a flesh-and-blood boogeyman, or even a workaday occult chiller. There is something irrevocably, inexplicably wrong with the world in Longlegs, like an insidious black rot that has seeped up from Hell itself. The titular killer is merely a symptom of a far greater evil, and there’s no escaping its malignant touch. It’s already everywhere.

Perkins has played in this particular demonic sandbox before. His commanding debut feature, The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015), nestles a twisted tale of satanic devotion in a lonely, wintery New England that seems already half-sunk into Dante’s Cocytus. Whether he’s weaving a gothic ghost story (I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House) or revisionist fairy tale (Gretel and Hansel), Perkins consistently envisions a cosmos of porous (or outright nonexistent) barriers – between the natural and supernatural, the living and dead, the innocent and wicked. In the filmmaker’s conception, evil slithers freely through the shadows of a fallen Earth, uninhibited by notions of cosmic fairness or justice.

This is especially the case in Longlegs, which unfolds in a chilly, parallel-universe version of the 1990s, one where Clinton-era optimism has been swapped for a suffocating sensation of encroaching doom. The period setting is less about sidestepping potential plot speed bumps (e.g., smartphones) than about creating evocative spaces. The mid-’90s Oregon conjured by Perkins and his crew – production designer Danny Vermette, set decorator Trevor Johnston, and costume designer Mica Kayde – is still strewn with the sagging furniture and yellowing tchotchkes of the prior three decades. (Corresponding, neatly enough, to Longlegs’ reign of terror.) Much as in the Monroe-starring It Follows (2014), one is left with the impression of a civilization in decline, an America of stale rooms, vacant lots, and lonely roads.

Although this setting is eerily redolent in its particulars, what truly unsettles is the way that cinematographer Andres Arochi shoots it. He fills the frame with yawning black spaces and hazy light glowing in hues of bronze, brown, and smoke gray. The interiors feel suffocating, while the exteriors seem vast and exposed. Monroe’s heroine often looks maddeningly small and vulnerable, her back turned obliviously to a threatening void that might conceal unknown terrors. There are particular shots that feel like the filmmakers are explicitly yanking the chains of young horror fans, raised on a diet of Conjurings to anticipate a jump-scare from every negative space and reverse shot. It’s destabilizing in a devilishly gratifying way, a singular aesthetic approach in a horror landscape defined by so much sameness, of both the mainstream and arthouse varieties.

The film’s small supporting cast is in uniformly fine form. Underwood – who hasn’t seemed to have aged a jot in 20 years – brings a welcome warmth and exactitude to a thankless, no-nonsense boss role. Alicia Witt is distressingly mesmerizing (and almost unrecognizable) as Lee’s mentally declining mother. The Blackcoat’s Daughter star Kiernan Shipka pops up for a scene and steals the show as Longlegs’ only surviving victim, doing some wild accent work. Undeniably, however, much of the film’s potency hinges on its lead performers. Monroe plays Lee as a tight-lipped knot of anxiety and trauma, a woman who looks like she would be perpetually trembling if she weren’t clenching every muscle in her body so hard. It’s a far cry from the tough-but-vulnerable archetype one typically sees with female law-enforcement protagonists, particularly in this subgenre. Monroe resists every opportunity to humanize Lee through pat characterization, consistently portraying her as an awkward enigma, full of thousand-yard stares and formless guilt.

And then there’s Longlegs himself. Wrapped in an unholy quantity of prosthetics that makes him resemble the albino lovechild of Emperor Palpatine and Piper Laurie’s Margaret White, Nicolas Cage brings his usual larger-than-life energy to a fittingly bizarre character. Intriguingly, Perkins and his collaborators subvert the strangeness of Longlegs’ appearance through framing, blocking, and editing, rarely allowing the audience a clear, sustained view of a figure who would almost certainly attract stares in real life. Cage speaks in a breathless, singsong voice, cooing every line with the barely contained, syrupy delight of a proud grandmother. Around the margins of the character, he and Perkins suggest a pathology born at the perverse intersection of a purity-obsessed evangelical Christianity and the occult-tinged hedonism of rock ’n’ roll.

It’s a monstrously upsetting and borderline silly performance, but one that dovetails with Perkins’ interest in the myriad ways that the Devil operates in this world. Longlegs looks and acts exactly like a demon-haunted churchgoer’s mental picture of a child-murdering satanic acolyte, but there are many other subspecies of evil out there, some wrapped in the holiest of covenants and the purest of intentions. This, ultimately, is what disturbs about Perkins’ feature: Not the fact of the Devil’s existence, per se, but the notion that his gnarled hand can execute the most radical alterations, corrupting all that is good and decent. Not for nothing is the cover art of Lou Reed’s Transformer hanging prominently in Longlegs’ subterranean lair and workshop. (OK, that’s probably also an allusion to Lambs.) Satanic magic is left-handed, after all. It turns things backward, upside down, and inside out. Longlegs asks us to bear witness as the unthinkable becomes reality: guardians change into killers, gifts turn into curses, and birthday parties become bloodbaths.

Longlegs is now playing in theaters.