Unlike the idiom with which it shares a name, the 1934 standard “Blue Moon” is anything but uncommon. The song is especially prevalent throughout film history, with its earliest appearances dating as far back as the Marx Brothers comedy At the Circus (1939). The frequency of its use hasn’t flagged since. It’s unsurprising, given that writers Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart were, after all, contracted by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to write catchy songs for the studio’s big star vehicles. With Rodgers serving as composer and Hart on lyrics, the pair would go on to collaborate for the next quarter-century, writing some of the most recognizable love songs of all time, including 1932’s “Isn’t It Romantic?” and 1937’s “Where or When” and “My Funny Valentine.” And yet, nearly 90 years later, none of them is quite as iconic as “Blue Moon.”

However, the original lyrics — known simply as “MGM Song No. 225,” or “Prayer (Oh Lord, Make Me a Movie Star)” — belong to an entirely different song. Initially conceived for Hollywood Party (1934), MGM’s star-studded pre-Code musical featuring Laurel and Hardy, the Three Stooges, and even Mickey Mouse, the tune was envisioned for Jean Harlow. Riding the success of Red-Headed Woman (1932) and Dinner at Eight (1933), Harlow was to croon a wistful, heartfelt number Rodgers and Hart imagined as a young actress’s plea to the heavens for a chance at stardom:

Oh Lord, if you’re not busy up there,

I ask for help with a prayer,

So please don’t give me the airOh, hear me, Lord, I wanta see Garbo in person

With Gable when they’re rehearsin’

While some director is cursin’I wanta open up my eyes at seven

And find I’m standin’ in the Golden Gate

And walkin’ right into my movie heaven

While some executive tells me I’ll be greatOh, Lord, I know how friendly you are

So, if I’m not goin’ too far

Be nice and make me a star

Alas, Harlow and “Prayer” were ultimately cut from the film. Rodgers and Hart reworked the lyrics twice more, both times for Manhattan Melodrama (1934). (The second version, titled “The Bad In Every Man,” is the one the studio eventually settled on. Ironically, the film starred Clark Gable.) The following year, MGM again revised the third version into a fourth, this time hoping to dominate the radio waves with a commercial hit. Here the dynamic tune evolved into its final form: the melancholic love song “Blue Moon”.

Though the lyrics have transformed it into a torch song, it nonetheless feels as if the original intent of “MGM Song No. 225” has lived on through the use of “Blue Moon” in films about stardom. With its appearances in All About Eve (1950), New York, New York (1977), and Notting Hill (1999) — three exceptional films about the less glamorous aspects of celebrity status — it’s notable that the spirit of “Prayer (Oh Lord, Make Me a Movie Star)” lives on through “Blue Moon” long after the former was shelved.

In the spring of 1949, almost 15 years after Rodgers and Hart’s commercial cut charted in Variety’s Top Ten for four and a half months in 1935, two separate renditions of “Blue Moon” took up residence on the Billboard charts. Billy Eckstine’s swinging take and Mel Tormé’s jazzier interpretation were the first of many subsequent resurrections of the song in the years to come. This revitalization carried over into Hollywood, which had hardly touched “Blue Moon” since its last

appearance in At the Circus. In quick succession, film after film added Rodgers and Hart’s rediscovered classic to their tracklist. East Side, West Side (1949), Malaya (1949), All About Eve (1950), The House on Telegraph Hill (1951), With a Song in My Heart (1952), My Wife’s Best Friend (1952)… the list goes on, but the most poignant use of them all can be found in All About Eve.

Writer-director Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s masterwork, the film focuses on Margo Channing (Bette Davis): an aging Broadway star, newly 40, who fears that this might mark the end of her career as a leading woman. One night, following a killer performance of Margo’s latest, she is introduced to an adoring fan named Eve Harrington (Anne Baxter). Accompanied by Margo’s friend Karen Richards (Celeste Holm), the wife of playwright Lloyd Richards (Hugh Marlowe), Margo is won over by Eve’s

earnest reverence toward her. She hires her as an assistant, but soon finds that Eve has greater plans: to sabotage Eve’s personal life and steal her spotlight through her own formidable charms.

Though ostensibly about the theater, All About Eve can also be read as a scrutiny of the Hollywood star system of the midcentury. Now a couple of decades since the establishment of the studio system, a younger, newer generation of talent was on the rise around the film’s release in 1950. Margo Channing embodies the Golden Agers, whereas Eve Harrington represents the torrent of young blood flowing into the film industry as the blacklist grew longer and the studios faced an impending crisis. In this context, its use of “Blue Moon” — arriving toward the end of the famed “bumpy night” foretold in All About Eve’s most canonized quote — takes on a double meaning.

Backgrounding Margo’s discussion with Lloyd concerning his latest play-in-progress, twinkling on the piano in the other room while the two frankly discuss ageism on Broadway, the song’s original lyrics come to mind: “Oh, Lord, I know how friendly you are / So, if I’m not goin’ too far / Be nice and make me a star.” This prayer echoes the desires of both Margo and Eve: The former furtively pleading with her playwright to keep writing parts for her, the latter covertly trying to infiltrate Margo’s life and eventually her leading roles. “Blue Moon” is a tune pulsing with feelings of ambition and desire. It’s the perfect fit for All About Eve, one of the most exemplary portrayals of cutthroat ambition and ardent desire in the medium’s history.

Fresh off of Taxi Driver (1976), Martin Scorsese — still a relative newcomer to the director’s chair, with only a handful of films to his name — looked to avoid being pigeonholed by the masses by turning to something completely different from the dark, abrasive realism of his filmography thus far. Thus, New York, New York (1977) was born. Arriving 27 years after All About Eve, Scorsese — feasibly in direct reference to Mankiewicz’s film, given Marty’s extensive knowledge of the art form — again uses the theater as a stand-in for Hollywood. He even sets it around the same time as Margo and Eve’s power struggle, opening on V-J Day in 1945 and unfolding over several ensuing years.

Jimmy Doyle (Robert De Niro) is a slick, egocentric saxophone player in the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra — the resident band in a New York City nightclub currently celebrating the end of World War II. Serendipitously, in a sea of revelers, Doyle meets Francine Evans (Liza Minnelli) — a USO singer who clearly wants nothing to do with him but nonetheless winds up sharing a cab with him. Jimmy strong-arms Francine into tagging along to an audition, where the pair fortuitously land a job as a traveling musical act. Their rising fame and burgeoning romance mix like oil and water, an irreconcilable divide that redefines their future together.

Sandwiched between two of his most highly praised films, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull (1980), New York, New York was unquestionably a major risk for the director at the time. Its strategic employment of “Blue Moon” — which Jimmy and Francine’s rival singer Bernice (Mary Kay Place) covers with a jazzy, upbeat rendition — clues the audience in Marty’s motives with this throwback to the big-budget musicals of Old Hollywood’s (outwardly) halcyon days. Despite being set in the jazz scene of the late 1940s and early 1950s, New York, New York is decidedly a story about Scorsese and his New Hollywood contemporaries such as Brian De Palma, Paul Schrader, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas.

The third verse of the original lyrics to “Blue Moon” could appropriately describe the aspirations of all these studio system disruptors: “I wanta open up my eyes at seven / And find I’m standin’ in the Golden Gate / And walkin’ right into my movie heaven / While some executive tells me I’ll be great.” In this light, the diverging career paths of Jimmy and Francine speaks directly to the bifurcation of the so-called Film School Generation. They either soared to the upper echelons of the box office and earned a lifetime of blank checks… or barely made enough to score another shot under the close studio supervision. The critical success but commercial failure of Taxi Driver had Scorsese eying this fork in the road anxiously. New York, New York’s utilization of “Blue Moon” suggests he heard the lyrics to Harlow’s “Prayer” echoing faintly from movie heaven.

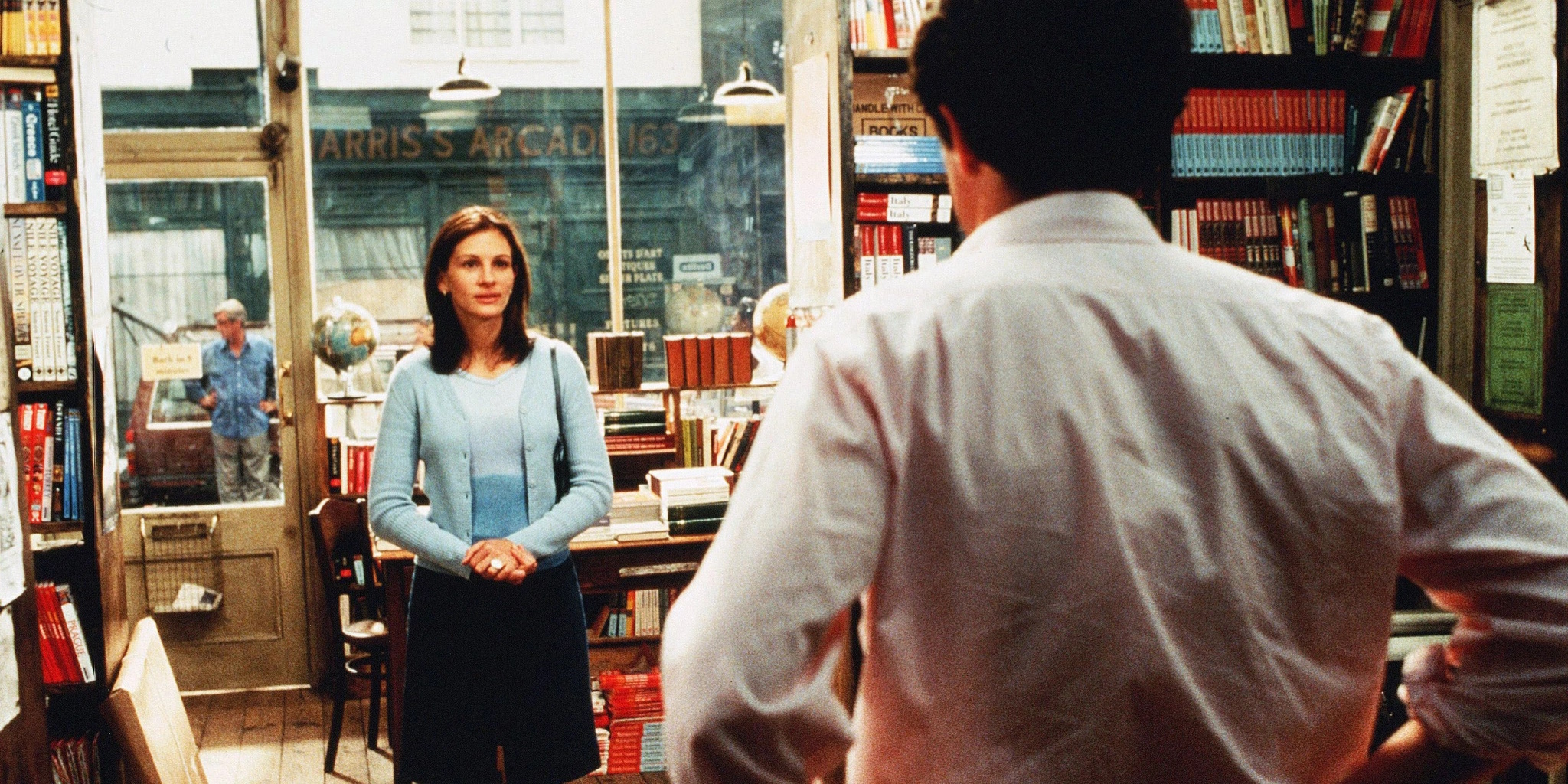

With the titans of the 1970s largely reined in after one of the greatest decade-long runs in the industry’s lifespan, the 1980s and ‘90s were all about downplaying the auteur theory and putting the attention back on the movie star — and trying to break box office records in the process. It was something of a return to form for the moviemaking business: With so many big studio pictures being made, it almost looked like the ’30s again. As it turned out, it was also the perfect time for an encore of “Blue Moon.” By the time of Notting Hill’s release, Hollywood’s blockbuster era was in full swing. Starring Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts as Will Thacker and Anna Scott, an average joe and a superstar actress who fall in love after a chance encounter in Will’s bookstore in the titular London district, the film earned over $360 million (the equivalent of $630 million today, adjusted for inflation).

In one of the film’s most somber scenes, not long after Will and Anna’s affair is leaked to the tabloids and the pair have seemingly split for good, Will’s friend Tony (Richard McCabe) is mourning a different kind of loss: That of his restaurant, which failed to take off and is now shuttered, leaving him hopeless and broke. Bernie (Hugh Bonneville) is in no better place, revealing to the group over their final dinner at Tony’s that he has been fired. Honey (Emma Chambers) is the only one with some positive news — she and Spike (Rhys Ifans) are engaged. An exceedingly bittersweet scene, made all the more so by the gentle glint of “Blue Moon” on the piano. It’s here that Max tells Will that Anna is back in London filming a new project — a sign of life at the end of a bleak, six-month-long stretch of solitude for Will.

In place of Harlow singing “Oh, hear me, Lord, I wanta see Garbo in person / With Gable when they’re rehearsin’ / While some director is cursin’,” Will imagines seeing Anna in a similar light on the set of the Henry James adaptation she’s currently shooting just outside the city. When he visits the set the following day in hopes of winning her back, “Blue Moon”s final lyrics make just as much thematic sense as the scrapped ones: “[Y]ou knew just what I was there for / You heard me saying a prayer for / Someone I really could care for / And then there suddenly appeared before me / The only one my arms will hold.” Regardless of how the scene plays out, this specific “Blue Moon” needle drop reintroduces the song to a new audience witnessing a new era of celebrity status unfold.

Where All About Eve uses the Rodgers and Hart track to wrestle with the old stars making way for the new and New York, New York to weigh commercial stardom and creative freedom, Notting Hill implements the standard as a way to consider a uniquely contemporary aspect of said celebrity status: the fantasy of parasocial relationships. Will and Anna’s entanglement is the stuff of dreams for the modern-day mass media consumer. To not only know an A-lister but also to fall in love with them? And they with you? The tabloids that effectively squashed their fling are the very same ones that perpetuate this artificial, one-sided closeness between the fans and the famous that has only gotten worse in the time since the film’s release. It’s as improbably idyllic as the scene described in the lyrics: “I heard somebody whisper, ‘Please adore me’ / And when I looked, the moon had turned to gold.”

Lyrically, “MGM Song No. 225” is quite a departure from the standard version of “Blue Moon” used in hundreds of instances across film and television since 1934. In spite of the different words, though, the actual tune is unchanged. Like the solid foundation of a home that has undergone rigorous interior renovations, one can still sense the spirit of what used to be even as they soak in the place in the present. This is true of Rodgers and Hart’s quintessential serenade, especially if one is aware of the original lyrics. The text has changed, but the feeling remains. Audiences now know it best as a nocturne both happy and sad at the same time, but — as All About Eve, New York, New York, and Notting Hill prove — “Blue Moon” functions just as well as a naive cry to the heavens for a shot at stardom, no matter the cost. That true cost is left unsaid (or, rather, unsung) in Rodgers and Hart’s track, but it’s hardly unknown.

Consider Jean Harlow. She never even got the chance to sing “Prayer (Oh Lord, Make Me a Movie Star)” as her songwriters intended, but her entreaty was nevertheless heard. The foremost blonde bombshell, Harlow remains an icon of American cinema at large — even 86 years after her death at the age of 26, following a strange string of illnesses and ailments ranging from sepsis to cerebral edema to outright kidney failure. Coincidentally, her final film Saratoga (1937) saw her costarring alongside close personal friend Clark Gable — the very Gable Rodgers and Hart would’ve had her praying for just several years prior. It’s a poetic coda, but not exactly a feel-good Hollywood ending. In fact, of the three films discussed at length here, the only title that fits such a bill is Notting Hill — the one that is, for all intents and purposes, the most like a fairy tale. (Even so, its depiction of fame doesn’t seem all that desirable.)

So why is this particular song paired with this particular subject, again and again, generation after generation? For one, it just feels right. “Blue Moon” sounds like heartbreak — a skipped heartbeat, a regretful pang, a drop of the stomach — making it the ideal score for any film pertaining to hopes and dreams and the inevitable disappointment that follows them. More precisely, the song speaks to the unlikely luck of actually making it big, and doing so in a way that also maintains a sense of authenticity or of self. Ironically, the song itself underwent substantial rewrites to become more commercially accessible, something that left Rodgers and Hart dismayed. Such is the pattern with many of these cautionary Hollywood tales: Artistic integrity versus mass appeal. Artistry versus profit. Reality versus artificiality. Whether All About Eve, New York, New York, or Notting Hill, one can’t help but think of an unanswered prayer as far preferable to the devastating price of fame.