[Note: This essay was originally published at Cinema St. Louis’ The Lens.]

There is a sneaky perversity at the heart of Ted Kotcheff’s masterful 1971 feature Wake in Fright, one quite apart from the film’s harrowing depiction of illegal gambling, drunken hooliganism, and kangaroo slaughter in the Australian Outback. Most stories about a journey into the heart of darkness involve a character who either travels outward into the lawless wilderness, or inward into the beating heart of the Big City. John Grant, the young schoolteacher protagonist of Wake in Fright, does neither. His heart of darkness is unearthed at the halfway point of his physical journey. In a droll subversion of most stories of self-discovery, John’s plunge into his primal nature unfolds at a waystation between nowhere and somewhere. Despite the shabby banality of this unremarkable midpoint – or, perhaps, because of its invigorating liminality – it manages to trap him as surely as flypaper glue ensnares a wriggling insect.

Like many Australian teachers of the era, John is burdened with a hefty government debt from his post-secondary schooling, and this commitment has shackled him to a posting in the middle-of-nowhere hamlet of Tiboonda. This place is a mere flyspeck on a map, consisting of little more than a one-room schoolhouse, a tumbledown hotel, and a bare-bones train platform without a working clock. John’s forthcoming Christmas holiday promises a reprieve from this desert gulag, and the viewer can practically taste his anticipation as he packs his bags and boards a train for the regional airport, dreaming of the ocean breezes and lovely girlfriend that await him in Sydney.

Unfortunately, John will never make it to his flight. While staying overnight in the mining town of Bundanyabba, he is drawn into a nightmarish netherworld of dissolution and violence, partly through cruel happenstance and partly through his own reckless choices. Compared to Tiboonda, “the Yabba” – as the locals call it – is practically a cosmopolitan metropolis, juiced by a recent zinc boom. (The town is, in fact, a thinly disguised stand-in for Broken Hill, New South Wales, which is where the film’s exteriors were shot, and which also inspired author Kenneth Cook’s original 1961 novel.) However, the Yabba is no Sydney. It is rough and jagged, perched on the precipice of the scorching rangelands of South Australia and perpetually dripping with filthy sweat. It has a peculiar, dusty gravity, this town, as John ultimately discovers to his ruin.

Although it premiered at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival and was well received in the U.K. and France, Wake in Fright was a disappointment at the Australian box office. Anecdotally, the film is thought to have turned off some Aussie viewers with its absurd, violent depiction of Outback life. Kotcheff himself is Canadian and several key crew members were British, and there may have been a sense that the film was engaging in exploitative mockery of the Commonwealth’s rough-edged Southern cousins. However, Wake in Fright was a joint Australian-American production, and the film was shot almost entirely in Broken Hill and Sydney. Along with Nicholas Roeg’s contemporaneous Walkabout (1971), the film would ultimately play a key role in jump-starting a New Wave in native Australian cinema. It would not be much of an exaggeration to say that without Wake in Fright, there is no Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), no Sunday Too Far Away (1975), and no Mad Max (1979).

Setting aside a meta-textual awareness of the feature’s place in history, however, it is simply inaccurate to assert that Wake in Fright is primarily interested in denigrating the allegedly uncouth culture of its Outback setting. Kotcheff and the film’s producers, for their part, were quite enamored with the people and landscape they encountered during the production. The filmmakers were reportedly insistent on verisimilitude, recruiting locals from neighborhood pubs as extras and relying on their Australian cast members to help them maintain the film’s grubby realism. These performers included the legendary Chips Rafferty (Mutiny on the Bounty) in his final film role and the soon-to-be-legendary Jack Thomspon (Breaker Morant) in his feature debut.

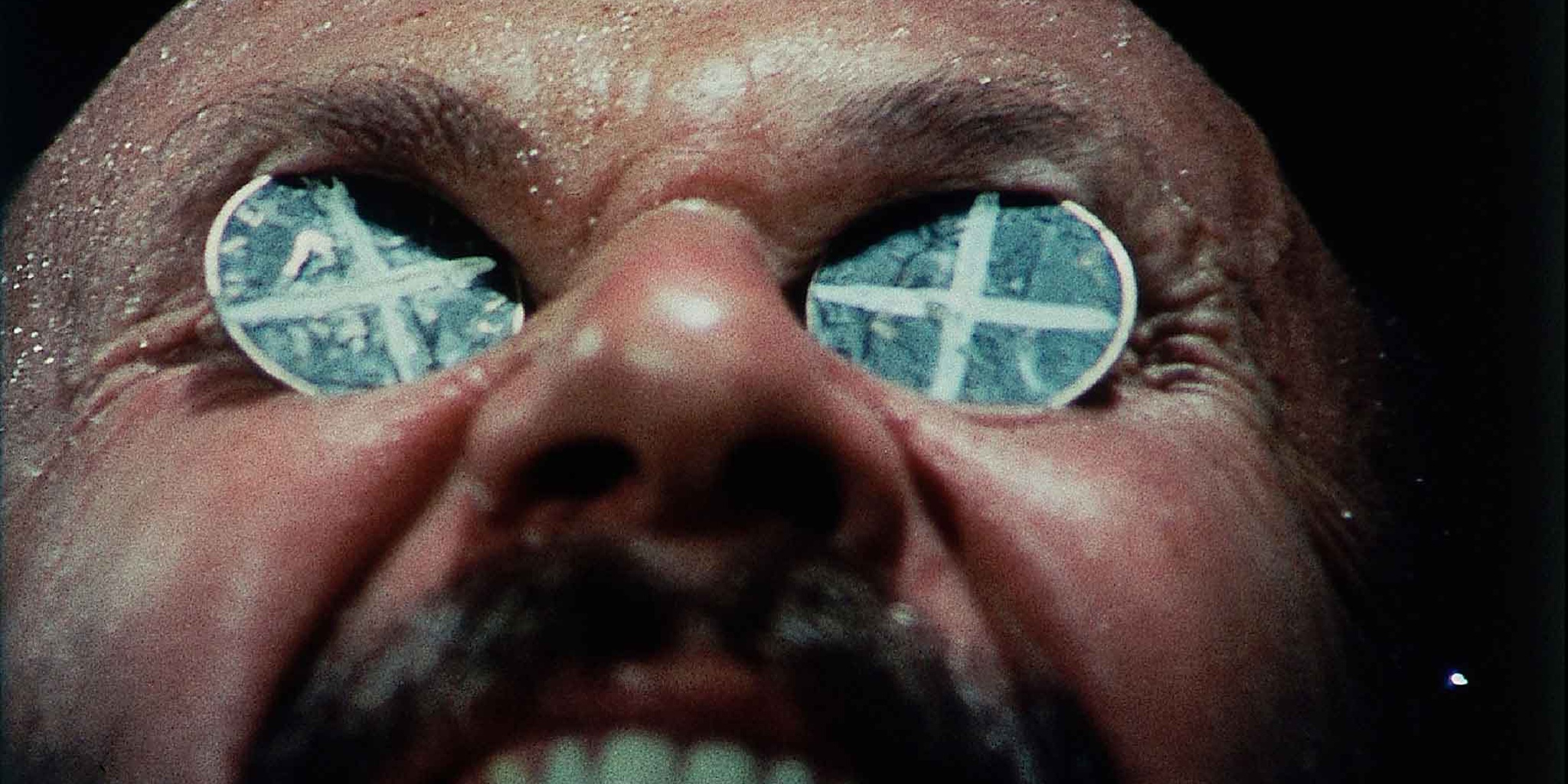

Even if one disregards artistic intent and focuses on the text, it should be obvious to most viewers where the feature’s critiques are directed. The film reserves its sharpest scorn not for the rough-and-tumble way of life that dominates in the Yabba, but for John, taking aim at his smug superiority, his seething resentment, and his insecure foolhardiness. In Donald Pleasance’s garrulous, harddrinking Doc Tydon, John is given a glimpse of his own potential future: a man derailed from a promising life by his own appetites in a place all too willing to indulge them. Pleasance – exuding a kind of sweaty, scumbag sexiness that compares to nothing else in his filmography – makes this possible fate feel at once seductive and repulsive. As John descends further and further into petty hedonism and brutality over the course of a long, dark weekend, Tydon becomes both his Virgil and his nemesis.

It is difficult to imagine what the typical American filmgoer might have made of Wake in Fright as it trickled into U.S. theaters in late 1971 and early 1972 – even with several of its most graphic and disturbing minutes lopped off. With its degenerate characters, squalid cruelty, and intimations of sexual violence, the film has an undeniable grindhouse vibe, but the nimble brilliance of its cinematic artistry makes it feel more Lincoln Center than Times Square. Although the film was thought lost for decades, the discovery of a negative and the feature’s subsequent 2009 restoration and re-release have fortunately widened its exposure. (It is, along with Antonioni’s L’Avventura, one of only two films to have played at Cannes twice.) Yet Wake in Fright’s identity remains a fiendishly slippery thing. Many contemporary critics refer to it as a horror film, but it could just as easily be described as a gritty drama, an Outback noir, or a quasi-psychedelic character study. Like many indelible works, it resists easy categorization, writing its own idiosyncratic genre in a vocabulary of booze, blood, and sticky, relentless heat.