Emerging from the nocturnal gloom of winter like a specter of Death itself, Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu is one of the most lavishly, relentlessly Gothic horror features that 21st-century cinema has birthed to date. Was there ever any doubt? The moment that the director’s surprisingly faithful remake of F.W. Murnau’s genre-defining Nosferatu: A Symphony of Terror (1922) was announced, it was a certainty that Eggers’ fourth narrative feature would aspire to immerse viewers in its authentic yet heightened 19th-century world. Rigorous focus on realistic period detail and evocative atmospherics have been Eggers’ most conspicuous calling cards, whether the setting in question is the demon-haunted Puritan New England of the 1600s (The Witch) or the fire-and-ice brutality of Dark Ages Scandinavia (The Northman).

However, what distinguishes the director’s peerless attention to detail from the extravagant yet shallow ambitions of glossier period pieces – the sort that win Best Costume Design Oscars and then vanish down the memory hole – is the method behind Eggers’ madness. Historical fidelity is simply a means to an end for the filmmaker, whose features aspire to convey not just the sights, sounds, and texture of a vanished time but also the worldview of the people who inhabit it. To those unfamiliar with the redolent power of his work, fussing over the weave of the wool in a late 19th-century lighthouse-keeper’s overcoat might seem like the nitpicky fixation of an auteur who has lost the plot. For Eggers, however, authenticity is like an incantation for a séance, a meticulous spiritual practice that aligns cast, crew, and audience alike with bygone worlds that are jarringly unfamiliar to the contemporary mind. His works aim to simultaneously resonate and alienate, their half-light revealing a few glinting, perilous handholds – those timeless human impulses like fear, guilt, and wrath – in the strange, forbidding country of the past.

Nosferatu, then, represents something of a departure for Eggers and his collaborators, as the silhouette that it casts, though monstrous in shape, is hardly obscure to contemporary viewers. As its original intertitles made explicit, Murnau’s silent feature is an unauthorized Germanic adaptation of Dracula, and there are few works of English-language fiction as deeply embedded in the pop-cultural consciousness as Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel. (The 1922 Nosferatu itself deserves a healthy share of the credit for this fact, alongside the 1924 Dracula stage adaptation and Tod Browning’s 1931 film.) Any contemporary filmmaker who aspires to create a “straight” adaptation of Dracula – or, in this case, a reimagining variously inspired by Stoker’s novel, Murnau’s film, and more than a century of Victorian-set Gothic-horror cinema – is obliged to wrestle with an obvious question. Why yet another Dracula film, and why now? This challenge has a particular urgency for Eggers, whose cinema is so fascinated with uncanny occult forces and the awful truths they reveal about us.

Unsurprisingly, the filmmaker approaches his film’s setting – Central and Eastern Europe in 1838, preserving the temporal and Teutonic relocation that 1922 screenwriter Henrik Galeen effected on Stoker’s story – with his typically high standards for every aspect of the production design. However, the world-building abetted by faithfully reconstructed corsets and cobblestones tells only half the story. Nosferatu’s identity as a Gothic horror film is, if anything, more essential than its status as a period piece, and nowhere is this more apparent than in Jarin Blaschke’s luminous nocturnal imagery. Returning for his fourth collaboration with Eggers – it was Blaschke who bestowed The Witch’s firelit scenes with the striking chiaroscuro glow of a Gerard van Honthorst painting – the cinematographer conjures night sequences in Nosferatu composed of the deepest blacks and midnight blues, the latter somehow glowing with a faint, unearthly opalescence. The feature’s fictional mercantile city of Wisborg might occupy a real-world historical space in the rapidly industrializing German Confederation of the 19th century, but its spiritual lineage is wholly indebted to Gothic cinema. This is not the literal past but literary Ere, a benighted realm of foggy streets, crumbling castles, and cobwebby tombs.

Nonetheless, the most striking thing about Nosferatu is not that it looks and sounds spectacular – although in our present age of tossed-off digital glop, the pleasures of a gorgeous, R-rated period horror feature should never be discounted – but that it injects new (un)life into one of cinema’s hoariest tales. The 127-year-old plot beats of this story might be as familiar as the background thrum of our own pumping blood, but Eggers bestows it with startling psychological vigor through a relatively minor shift in perspective and thematic emphasis. Plenty of adaptations have highlighted the darkling, symbiotic relationship between the vampire lord and the quaking maiden whom he covets, but none have approached it quite like Eggers. His Nosferatu is a pre-Freud Freudian nightmare: The story of a woman writhing in the sealed sepulcher of her own troubled, terrifying mind, long before anyone – least of all the clueless men who surround and infantilize her – could even put a name to her afflictions.

Ellen Hutter (Lily-Rose Depp) has struggled with a witch’s brew of overwhelming, irrational thoughts since she was an adolescent. Grotesque visions of death haunt her dreams, but she is less repulsed by these nightmares than by her own ecstatic reaction to them, which betrays something profoundly twisted about her soul (or so she believes). Ellen’s marriage to handsome, attentive real-estate agent Thomas (Nicholas Hoult) quelled these thoughts for a time, but her husband’s imminent business trip seems to have reignited them. Thomas’ employer, Herr Knock (Simon McBurney), has instructed him to oversee an obscure but wealthy Slavic nobleman’s purchase of a dilapidated manor in Wisborg, an endeavor that requires the young agent to visit this count at his ancestral castle in distant Transylvania. For Thomas, this task represents a ripe opportunity to ascend the social and economic ladder, but as her husband departs, Ellen feels a familiar, unmistakable dread rising in her throat.

We’ve seen this story a hundred times before, of course: the ambitious young man’s heedless journey into the superstitious East; a derelict castle that the local peasants dare not approach; a hospitable but eccentric nobleman who keeps odd hours and never seems to drink … wine. Eggers’ remedy to the mustiness of this scenario is to accentuate both the realism and otherworldliness of his setting. He strives to banish the cynical remove created by a century’s worth of homages, satires, and Halloween costumes through the sheer density of his Gothic atmosphere and through design choices that upend the viewer’s expectations. The Transylvania of this film is slightly fantastical, its shadows dense with profane secrets that the civilized world would just as soon forget. (The vivid descriptor from Murnau’s film never seemed more apt: “the land of thieves and phantoms.”) As in his other features, Eggers blurs the boundaries between reality and nightmare, disorienting both his characters and the audience. Does Thomas really witness a nocturnal ritual in which a Romani clan deploys a naked virgin as bait to exterminate some monstrosity slumbering restlessly in its grave? Or is his dreaming mind just inflamed by the clinging mist and lupine shapes that creep through the surrounding forests?

Nowhere is the filmmaker’s slantwise approach to the material more apparent than in the fearsome mien of Thomas’ host, Count Orlock (Bill Skarsgård). Elsewhere, Eggers liberally quotes from the visual design of Murnau’s feature – and, to a lesser extent, that of Werner Herzog’s 1979 version, Nosferatu the Vampyre – but this Orlock is something wholly original. Skarsgård’s Count echoes neither Max Shreck’s gangly, rodent-like fiend nor Bela Lugosi’s velvety aristocratic seducer. He resembles what he is: The walking, talking, 400-year-old corpse of a hereditary Wallachian warlord. He looks less like a genteel predator than a rotting twist of beef jerky, albeit one with the strength of an Olympic deadlifter. Nosferatu’s costume designers conceal Orlock’s towering yet shriveled form in a moldering, full-length cloak and high-crowned cap, lending him the profile of a monolithic gravestone. (While also underlining that the ferociously proud Count has never even contemplated changing up his 15th-century drip.)

If Orlock’s appearance is shocking, his voice is downright demonic. The sound mix on Skarsgård’s guttural, crypt-cracking bellow creates the unnerving illusion that the count’s words are emanating from every direction simultaneously. (Experiencing this sensation for oneself in a properly outfitted theater justifies the ticket price all on its own.) It seems to have a hypnotic effect on Thomas, who loses track of exactly where the count is standing in the flickering firelight of his great hall, a trick accomplished in-camera through some marvelous blocking and editing. The petrified Thomas hastily puts his signature on a strange document that Orlock pushes in front of him, and soon he is submitting to his host’s unusual appetites on a nightly basis, though his memory of these disturbing (and mildly homoerotic) encounters is hazy.

Like most Dracula adaptations, Nosferatu centers the action primarily on the count’s callow guest-cum-prisoner during its first act, then shifts its focus to the woman he left behind – mimicking the hunger that drives the vampire lord across storm-wracked seas toward the object of his desire. There’s a pleasure in watching as the characteristically exceptional Hoult bumbles way through the film’s never-was Transylvania with a brittle combination of stiff-lip resolve and tearful terror, but Eggers’ version of the story is really Ellen’s story. She is convinced that a terrible shadow is encroaching on her far-flung husband, a darkness somehow unleashed years ago by her own repressed perversity. The chronology of this delusion might be nonsensical, but the despair, nightmares, and oddly orgasmic fits that bedevil Ellen are very real.

These symptoms alarm the Hardings, the wealthy friends hosting Ellen during Thomas’ absence. The pregnant, God-fearing Anna (Emma Corrin) is concerned for her friend’s health, but new-money husband Friedrich (Aaron Taylor-Johnson, perfectly cast) is mostly just annoyed that all this womanly hysteria is disrupting the perfect Victorian order of his household. Rounding out the ensemble in Wisborg are Dr. Wilhelm Sievers (Ralph Ineson), a well-intentioned but out-of-his depth physician tasked with treating Ellen’s ailments, and Albin Eberhart von Franz (Willem Dafoe), a flamboyant, disgraced former professor of Sievers who knows a thing or two about the occult. It is von Franz who ascertains that a malevolent entity has fixed its baleful eye on Ellen from afar, lured by her uncommon sensitivity to the spiritual vibrations of the world.

For Ellen, however, Orlock is more than an ageless supernatural predator with dark designs on her dove-white neck. He embodies the root of her overpowering shame, the twinned serpents of Eros and Thanatos that coil around her soul. He represents all the morbid, shameful compulsions that Ellen has spent most of her life feverishly tamping down. These intrusive desires are nothing so straightforward as the animal lust that early Victorian society refuses to even acknowledge in its women – though sex is certainly part of the equation. Ellen’s anguish comprises a self-annihilation urge that seems utterly abominable in a world that is still decades away from the phrase “death drive.” It’s an impulse as forbidden as her most depraved carnal urges, which is why sex and death are indivisibly mingled in her sweaty, nocturnal thrashings. Orlock is not just a vampire: He’s an embrace from a putrefying corpse, a dust-dry fuck on a sarcophagus, a spider crawling up a morgue-cold thigh.

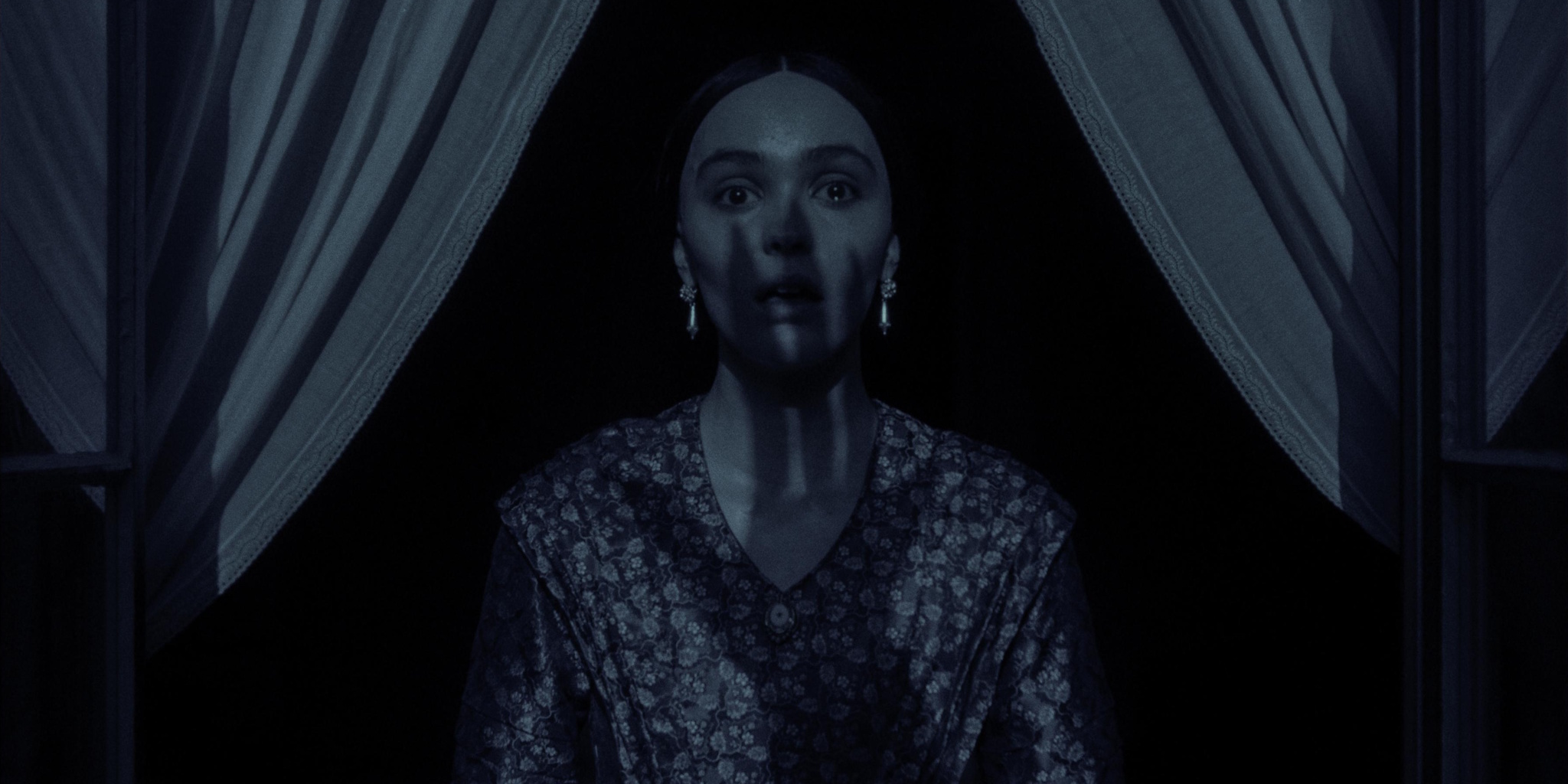

Depp is shockingly excellent as the clammy, quavering axis around which Nosferatu revolves, delivering a fittingly raw and intensely physical performance. The entire film is, in a sense, Ellen’s nightmare – Thomas’ captivity in Transylvania playing a bit like her fever-addled, self-loathing visions of the torments her poor husband would experience if he ever learned what a monster she truly is. Although Eggers generally preserves the ending of Murnau’s feature, he implements a subtle but crucial shift in motive that reframes Ellen’s fate. In 1922, Greta Schröder’s damsel-in-distress was deployed as a virginal deus ex machina at the film’s climax, while in 1979, Isabelle Adjani took on a more active, “fine, I’ll do it myself” role in defeating the count. This Nosferatu imagines not a virtuous maiden served up as a sacrifice but a defiant act of self-actualization: an eager bride opening her bedchamber door to Death incarnate, welcoming him as if he were an old lover.

Nosferatu opens in theaters everywhere on Wednesday, Dec. 25.