Lisandro Alonso is often cited as one of the reigning masters of slow cinema, but this perhaps undersells just how defiantly unconcerned the Argentine filmmaker is with hewing to the conventions of the international arthouse. His films are elusive, like meandering, slightly melancholy dreams whose meaning slips through your fingers at dawn’s first light. He experiments with narrative and documentary forms, resisting straightforward categorization even when he’s explicitly evoking genre, such as in Jauja (2014), his gorgeous, bewildering, Jodorowsky-tinged reimagining of The Searchers. He makes films about seekers, although their journeys are often silent and solitary. (And occasionally sedentary, as in his 2006 sort-of ghost story, Fantasma.) Even the most enthusiastic and open-minded cinephile might balk at the mutinously deliberate and opaque character of Alonso’s work. Yet there’s a reason that Cannes has essentially reserved a slot for him ever since he made a modest splash at the festival with his 2004 feature Los Muertos. No one else is making films quite like this.

The director’s latest feature, Eureka, is both perfectly consistent with his prior films and something bracingly new. It’s an anthology film of sorts – or, more accurately, a lopsided triptych, one that drifts across genres, places, and times. Like much of Alonso’s work, it is concerned with identity, colonialism, and the Global South, albeit in a way that is poetic and ruminative rather than politically didactic. Viewers hoping for some uncharacteristic clarity from this notoriously difficult filmmaker will be disappointed. Eureka isn’t interested in telling the viewer exactly how they should feel about global inequality and the systemic oppression of Indigenous peoples. It’s more akin to a vision quest than a righteous political tract: It juxtaposes three seemingly unconnected stories and provides the viewer with the space to ponder the dynamics that recur in different places and eras. “Time is a fiction, invented by men,” declares one character, which is about as explicit as Eureka ever gets.

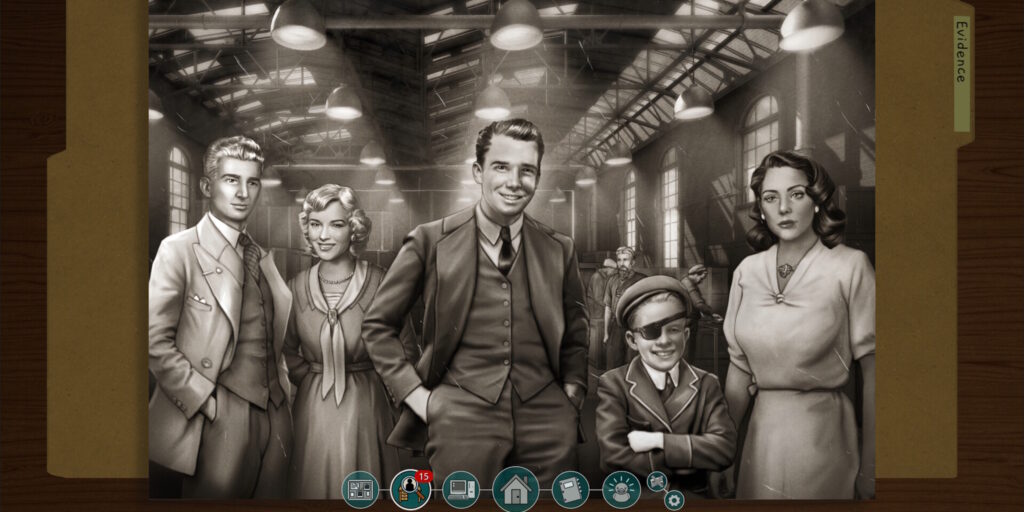

In the film’s first segment, Alonso provides a decade-later spiritual epilogue to Jauja, as a dusty gunslinger named Murphy (Viggo Mortensen) arrives in a corrupt frontier town to put down the malefactors that years ago kidnapped his daughter. This chapter’s exquisite black-and-white cinematography and faintly surreal atmosphere evokes Jim Jarmusch’s masterful acid Western Dead Man (1995), but Alonso’s approach isn’t quite as satirical, even if it’s hard to know just how seriously to take his over-the-top portrayal the American West’s degeneracy and violence. Inebriated citizens lie sleeping in the dirt streets, cowpokes drink from the same well where prostitutes bathe themselves, and gunshots ring out so frequently that the town sounds like a war zone – which, one supposes, it is.

This segment is the most narratively conventional of the three, and also the briefest. Mischievously, Alonso denies the viewer a satisfying narrative resolution to Murphy’s quest with a bit of formal trickery: The camera abruptly pulls out to reveal that this Western tale is, in fact, a late-night movie playing on a television. We are now in the present-day living room of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation police officer Alaina (Alaina Clifford) and her niece, Sadie (Sadie LaPointe), a youth-basketball coach. Alaina is about to leave for her evening shift patrolling the blizzard-lashed highways of the South Dakota reservation, and the bulk of the second segment concerns the disheartening experiences of these two women over the course of one modestly eventful night.

This chapter of the film is the longest and most compelling, partly due to the raw, tender-hearted performances from newcomers Clifford and LaPointe – who hold their own alongside veterans like Chiara Mastroianni – and partly due to how much genuine interest Alonso exhibits in his setting. He and cinematographers Timo Salminen and Mauro Herce capture the stark alienation that creeps into institutional spaces such as a police station or high-school cafeteria in the wee hours of the night. Yet the filmmakers also conjure a horror-adjacent tone at times, such as when Alaina interrogates addicts in a roach-infested flophouse or attempts to ascertain the intentions of a stalled motorist on a dark stretch of road. This middle segment of the film is often eerily, unconventionally beautiful. No sweltering tropical river or glacier-clad mountain in Alonso’s filmography has ever looked quite as arresting as a long, tense, noir-kissed shot in which Alaina slowly and silently surveys a trashed casino hotel room, searching for lingering perpetrators.

Eventually, Eureka shifts yet again, this time through an unexpected, transformative flourish of magical realism. With some assistance from her elderly grandfather, a distraught Sadie escapes the confines of reservation life and journeys (in a way) across time and space. Now we are in the tropical forests of Brazil during that nation’s military dictatorship of the mid-1970s. A small community of Indigenous dreamers meet daily to discuss their visions with a shaman, but even in this comparative Eden there are seeds of dissatisfaction and resentment. A love triangle leads to a scuffle and an apparently fatal stabbing, and the guilty man (Adanilo) is forced to flee and eke out a living as a day laborer at a nearby gold-panning operation. There, however, he soon falls ill and is singled out as a target for robbery by the other, non-Índio workers, leading to another desperate (and perhaps naïve) escape attempt.

This third chapter is the dreamiest and slowest segment of the film, and – as is the case with most of Alonso’s features – it concludes in a way that feels gravid with meaning and yet wholly perplexing. The filmmaker is famously reluctant to explain his intentions to either his actors or his audience. Accordingly, viewers are left to draw their own conclusions about Eureka and the deeper truths it attempts to plumb. Unquestionably, a thematic fascination with entrapment and escape runs through the film. Different kinds of colonial violence and power are in evidence in the feature’s three segments, each of which is concerned with the prisons constructed around people by history and myth. (A notion literalized in uncharacteristically direct manner by a brief pit stop at the Black Hills’ still-in-progress Crazy Horse Memorial, where the Oglala leader’s countenance is surrounded by construction equipment and chain-link fencing.)

Still, a dozen different filmgoers will likely draw a dozen different meanings from Eureka. Although that ambiguity may frustrate some, Alonso’s artistic hand has never felt steadier, formally speaking. Similarly, his languorous approach has never felt more attuned to his story’s emotional and thematic purpose. The director’s 2008 film, Liverpool, is both mesmerizing and maddening: It is perhaps the most incident-free work of 21st-century cinema that can still be legitimately described as a narrative feature rather than an outright avant-garde provocation. Here, however, Alonso uses stillness and silence (and occasionally both) for potent evocation. In one deceptively riveting sequence, Sadie sits idly at the tribal police station, listening in growing, impotent anxiousness as the dispatcher in the next room repeatedly calls out her aunt’s identification number, without receiving a response. It takes a minute to realize the brilliance of the gesture: From the raw materials of a woman waiting in a hallway and an off-screen voice repeating the same phrase over and over, Alonso has created a cunning reverse shot of a traditional police-thriller sequence. It’s enough to make a slow-cinema enthusiast swoon.

Eureka opens in select theaters on Friday, Sep. 20.