During the first two-thirds of Tilman Singer’s sophomore film, Cuckoo, the vibes are impeccably odd. Even before openly bizarre things begin to happen, everything in the frame feels wrong. The film seems to occur in an indefinite time and place. We’re somewhere in the Bavarian Alps, but how far we are from civilization remains uncertain. We’re sometime in the era of smartphones, but a cassette-tape answering machine — those died out in the mid-1990s, didn’t they? — figures significantly in the story. And everyone, save the focalizing character of Gretchen (Hunter Schafer), is acting really, really weird.

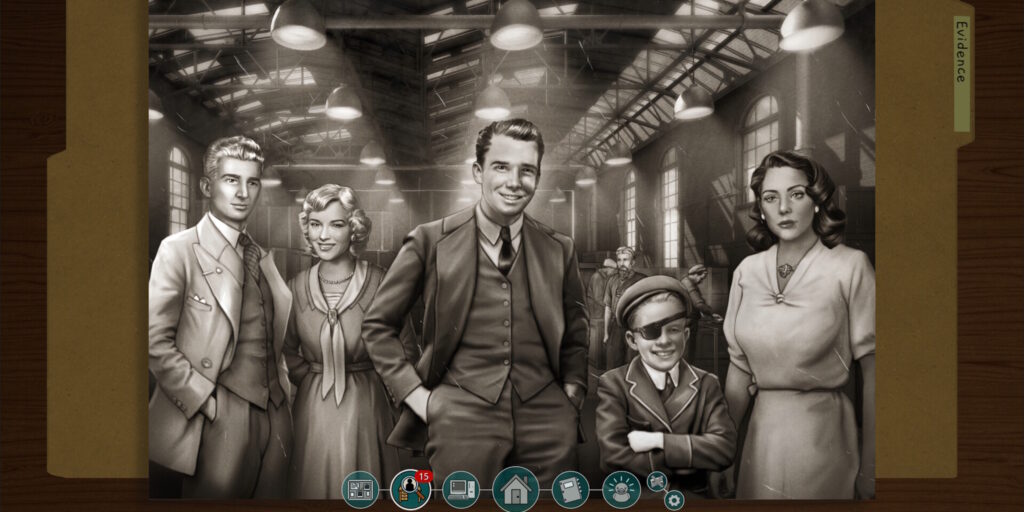

Gretchen has come to this “resort” (which depicts no evident amenities aside from remoteness) because her mother has died suddenly. She’s just barely still a minor, and that means her father Luis (Márton Csókás) has jurisdiction over her for the immediate future. Luis, who has started another family and basically put Gretchen out of his mind, brings her, his wife Beth (Jessica Henwick, underused), and their mute, preadolescent daughter Alma (Mila Lieu) to the Alps to work. He is an architect or something, there to realize a new phase of the resort, and he and Beth are chummy with the resort’s owner, König (Dan Stevens, beyond reproach).

It’s clear enough that Gretchen is an interloper right from the start. Her androgyny and her hostile aura (Schafer embodies the angsty teenager flawlessly) contrast particularly with Beth, a sweater-set-and-pearl-studs type, but also with the uncanny serenity of König and the resort as a whole. To attain money to return to the States, Gretchen begins work at the front desk, where she contrasts further with the other worker there, Trixie (Greta Fernández), a local femme with minimal interest in the resort’s mysteries. These include odd noises, unusual rules, guests wandering zombielike and half-dressed through the lobby, and an incredible lack of business.

After she meets Henry (Jan Bluthardt), a sweaty, paranoid policeman, her interest in what’s going on at the resort displaces her motivation to leave. Alma’s health meanders downhill, landing her in the hospital for seizures. Because Luis and Beth have decamped there as well, Gretchen becomes even more isolated, vulnerable both to König’s murky intentions and Henry’s single-minded pursuit.

Relatively early on, the film offers up its most interesting cinematic tic: a looping sequence, often the same take played three times, that coincides with a horrific screeching sound coming from the woods nearby, an extreme closeup of a neck’s fluttering pulse, and some kind of neurological disruption in people who can hear the sound. This occurs several times in the film, with varying effects on the people in the scene, and it signals the film’s monster. That monster is the biggest letdown in Cuckoo, because so little about its appearance is as bizarre as the film’s special, crooked vibe promises it would be. Its methods and motivations, as well as certain practical questions about living conditions, etc., remain unresolved.

Thematically, Cuckoo is simple enough: it’s about mothers and daughters, about the severe danger of breaking that bond. That’s it, that’s the movie. The nature of König’s scheme inserts some commentary about preservation, but it’s not compelling, in part because he’s so clearly villainous and in part because it has nothing to do with our IRL rapidly de-diversifying biosphere.

In some senses, Singer has assembled his second film by standard movie rules: apparent

setup/knockdown, detectable three-act structure, Chekhov’s butterfly knife. But in other ways,

it’s a film that resists rather than typifying horror. We understand Gretchen in a way we rarely

understand a final girl in a horror movie, not just rooting for her by default, but due to distinct

characterization. She’s in real pain, grieving her mother and the rapid explosion of the life she’s

known, and Luis treats her with appalling indifference. None of the deaths are juicy or fun, and

it’s frightening by virtue of lengthy, ghastly actions rather than music stings.

Despite this refreshing pushback against expectations, the third act is hard to like. It comes down (in part) to two men shooting guns at each other, which is of no interest to anyone who was totally digging the first two acts. Plus, Gretchen’s pivot regarding Alma has all the foundation of a six-inch stiletto heel. It’s necessary for the story, but that’s about it.

Anyone who knows the deal about cuckoos being brood parasites can guess at some of this film’s twists, but the plot is the least interesting thing about Cuckoo. The twists, the resolution (of sorts), and the look we finally get at the disruptive title creature don’t compare to the delicious weirdness of how the film feels. The closest comparison to those first two acts is either David Lynch on his best behavior (e.g. The Elephant Man) or The Shout, a film only tethered to regular human life rather than anchored by it. A film that feels so very off is not the product of a teachable skill. It’s an art, and no number of disappointing endings or unimpressive creature designs will dim its glow.

Cuckoo is now playing in theaters everywhere.