In 1963, a young photographer named Danny Lyon – then a rising star of New Journalism and an in-house documentarian for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee – began hanging out with a venerable Chicago-area motorcycle club, the Outlaws MC. Lyon rode with the Outlaws off and on for roughly four years, entranced by their machismo, camaraderie, and distinctly American dedication to the hazily defined “freedom” of their lifestyle. All the while, he took countless photos and recorded numerous interviews with members and hangers-on. Ultimately, Lyon became disillusioned with the club and the sinister changes that he observed in its culture. In 1968, he published his collected work on the Outlaws as The Bikeriders, a kind of photojournalistic fraternal twin to Hunter S. Thompson’s nonfiction novel Hell’s Angels. Although little noticed at the time, The Bikeriders eventually became a sought-after exemplar of the form – long out of print, it was republished with much fanfare by Aperture in 2014 – and Lyon went on to become one of the most laureled photographers of his generation.

For more than a decade, filmmaker Jeff Nichols (Mud, Loving) had reportedly been kicking around the idea for a 1960s-set biker film inspired by Lyon’s book. Although “based on the photography book of the same name” isn’t the kind of credit that normally inspires enthusiasm, Nichols is a keen-eyed and deeply humanistic screenwriter who has a knack for finding the aching heart of a story, regardless of tone or genre. To be sure, his film version of The Bikeriders heavily fictionalizes Lyon’s book. The Outlaws are now the Vandals, and the feature’s characters are, at best, loosely inspired by the sort of larger-than-life personalities that the photographer encountered. Yet Nichols – who remains one of American cinema’s most shamefully underrated writer-directors – zeros in on the twin essentials of Lyon’s work and its historical context. The Bikeriders deftly conveys the addictive ecstasy of belonging, the rush of finding a circle of like-minded obsessives that value loyalty, passion, and independence. However, Nichols’ feature is also about the inevitability of dissolution, the ironclad certainty that anything of value will be infiltrated, corrupted, and wrested away from those who value it. Nothing lasts forever, same as it ever was.

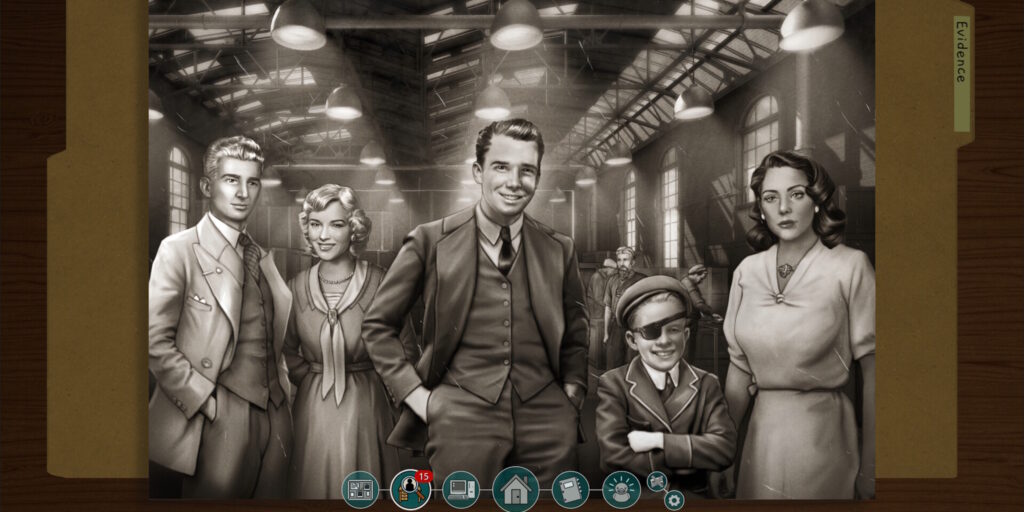

Nichols frames his flashback-heavy film as a series of interviews being conducted by a fictionalized version of Lyon, portrayed by Challengers’ Mike Faist. Although broadly chronological, The Bikeriders unfolds like a rambling history as recalled by its chain-smoking, possibly unreliable participants. The feature’s key interlocutor is, it turns out, not a club member at all, but loquacious biker girlfriend-turned-wife Kathy (Jodie Cormer). In the early 1960s, Kathy is a somewhat naïve, uptight young woman when she first enters a Chicagoland Vandals bar with some friends. By the end of the night, however, she is riding home on the back of a motorcycle owned by a dreamy, splendidly coiffed Vandals bad boy named Benny (Austin Butler). And that, as they say, is that: For the rest of the decade, the Vandals become Kathy’s de facto family, well before she and Benny actually tie the knot.

The half-step-removed perspective of Kathy – who is warmly embraced by the Vandals but, as a woman, perpetually on the outside of its masculine, violence-tinged culture – is key to The Bikeriders, much as the viewpoint of Karen Hill was essential to Goodfellas (1990). Indeed, given The Bikeriders‘ informal voiceover narrative, vintage rock ’n’ roll soundtrack, and Scorsese-esque stylistic flourishes, Goodfellas was almost certainly on Nichols’ mind when making his latest feature. Not that this is not necessarily a bad thing: Filmmakers trying their hands at their “Goodfellas movie” gave us Boogie Nights (1997), City of God (2002), and Lord of War (2005), among many other worthy features. Although The Bikeriders might not be the most aesthetically adventurous example of this particular sub-sub-genre, Nichols apprehends that the conceit of a years-later retrospective – both the romantic nostalgia and disillusioned hindsight – is crucial to understanding the arc of his subject, dramatically and historically.

Much as Goodfellas depicted mobsters who grew up watching gangster pictures, The Bikeriders presents an American motorcycle culture that had already become self-reflexive. The real-world Outlaws date back to 1935, but Nichols fixes the origin of the Vandals in the late 1950s, when working-class family man Johnny (Tom Hardy) happens to catch The Wild One (1953) on television and is forever changed. Johnny and his pal Brucie (Damon Herriman) found the Vandals as an enthusiast club, its membership consisting of regular joes who love motorcycles and the frontier spirit they embody. Like almost all organizations, however, the Vandals soon expands to include various outsiders and oddballs such as Zipco (Michael Shannon), a rangy, loose-screw Eastern European drifter who rails against “pinkos” in broken English. Then there’s Benny, a fiercely loyal younger member who projects the kind of insouciant, Brando-esque cool that Johnny idolizes. The latter has not-so-secret plans to name Benny as his successor, but the kid is more of a lone wolf than a leader, and it’s hard to imagine anyone but Johnny keeping the rowdier Vandals such as ginger grizzly bear Big Jack (Happy Anderson) in line.

For her part, Kathy initially enjoys the wild, slightly dangerous lifestyle of the club, while maintaining a healthy skepticism about the fundamental immaturity and recklessness of the men that surround her. When she finally marries Benny, it’s less about domesticating him than creating a bond that might compete with the claim that Johnny seems to have on the kid’s soul. Gradually, however, as the ranks of the Vandals swell and franchises pop up across the nation, Johnny’s cult-of-personality is diluted and his authority begins to erode. Stranger and more dangerous characters start appearing with Vandals patches on their jackets, such a California-dreamin’ psycho named Funny Sonny (Norman Reedus) and a jumpy, resentful young Turk known only as The Kid (Toby Wallace). Club picnics where children were once welcome mutate into shady house parties packed with drug addicts and white supremacists. Once this change has occurred, it seems impossible for the increasingly paranoid yet impotent Johnny to reverse course. The thing he built is no longer his thing.

The Bikerriders is, at bottom, a tragedy about this unraveling, about the tipping point when something that was once fun becomes, well … not fun anymore. The film can sometimes feel a bit shapeless, structurally speaking, lurching from one conflict to the next without a clear sense of rising dramatic tension. Nichols also hems and haws a little about who the story’s “real” protagonist should be: Kathy, Benny, or Johnny. Admittedly, these qualities may be somewhat by design. There’s no single moment where everything changes definitively, and no single person is wholly responsible for the end of the Vandals’ golden era. Things change by increments, silently and invisibly. One night, Kathy looks around at a gathering and realizes that she doesn’t recognize any of the creeps leering at her, and that she no longer feels safe with the Vandals. She has the good sense to get out while she still can, but there will always be a warm, bittersweet tinge to the memories. It was fun while it lasted.

The Bikeriders opens in select theaters on Friday, June 21.