What makes a place special to us in a deeply personal way? It’s usually something more than the physical space that it occupies, more than the mere experience of its sights, sounds, smells, and textures. It’s a connection, an emotional bond with some essential or treasured aspect of our identities. Yet places are always changing. Time seeps into the cracks, tearing down and building up and tearing down again. Suddenly, the place where you grew up – or the place where you raised your children – is so dramatically transformed that it feels like a foreign country, one haunted by the displaced ghosts of your memories. We return to old stomping grounds on a cloud of nostalgia, only to be sideswiped by time’s arrow: This must be the place, and yet nothing is the same.

Brazilian filmmaker Kleber Madonça Filho (Bacurau) is keenly attuned to this melancholic phenomenon, and his new documentary feature, Pictures of Ghosts, is a compelling exploration of its discombobulating contours. Madonça begins his excavations in the apartment in downtown Recife where he once dwelled with his mother, and which he eventually occupied as an adult alongside his own wife and children. From there, the film spirals outward into the formerly thriving cinematic culture of downtown Recife, which was once packed with movie houses where sold-out crowds devoured the latest Hollywood releases, international hits, and the occasional art film. Those several square blocks of gleaming marquees proved to be fertile soil for Madonça’s adult life, as he eventually parlayed his adolescent cinephilia into a career as a critic, writer, and director.

Pictures of Ghosts is, in part, an elegy to these places: the cozy, breezy apartment sanctuary that cradled Madonça’s family for decades, and the surrounding community of movie lovers who kept The Godfather running 24/7 for a month straight in 1972. An unmistakable sorrow for what has been lost clings to the filmmaker’s reveries, but fortunately his documentary proves to be much more than a platform for a fifty-something man to grouse about the inexorable march of time. Within the specifics of the filmmaker’s own vividly recalled experiences, Madonça’s feature discovers the universal pangs that we all feel when we revisit our special places and are confronted by uncanny, staggering changes.

Madonça divides Pictures of Ghosts into three chapters, and this structural conceit is one of the film’s few fumbles: It doesn’t add much to the presentation, other than smoothing over the filmmaker’s choice to begin his time-tripping walkabout in his family’s old apartment. A single parent and progressive academic studying Brazil’s abolitionist movement, Madonça’s mother celebrated her independence by furnishing their second-floor home according to her eclectic tastes. She allowed Madonça’s brother, who was then studying architecture, to oversee the apartment’s renovations, resulting in a charming modern-meets-equatorial space that has stood the test of time.

In a move that was as much about frugality as aesthetics, Madonça often used the apartment as a backdrop for his filmmaking, beginning with the gory horror shorts he shot on home video as an adolescent. He continued this approach throughout his career, with the apartment playing a central role in his celebrated features such as Neighboring Sounds (2012) and Aquarius (2016) (which immortalized his real-world neighbor’s perpetually barking dog). Madonça establishes a sensibility of temporal dislocation by cutting irregularly between old home videos, behind-the-scenes snippets, clips from his finished films, and present-day footage. In this way, he ushers the viewer into a semblance of his own haunted headspace: In this place, it is every year all at once. Here Pictures of Ghosts introduces a tinge of the metatextual, as past and present, memory and cinema begin to smear together – The Beaches of Agnès (2008) with a twinge of middle-age angst rather than august reflection.

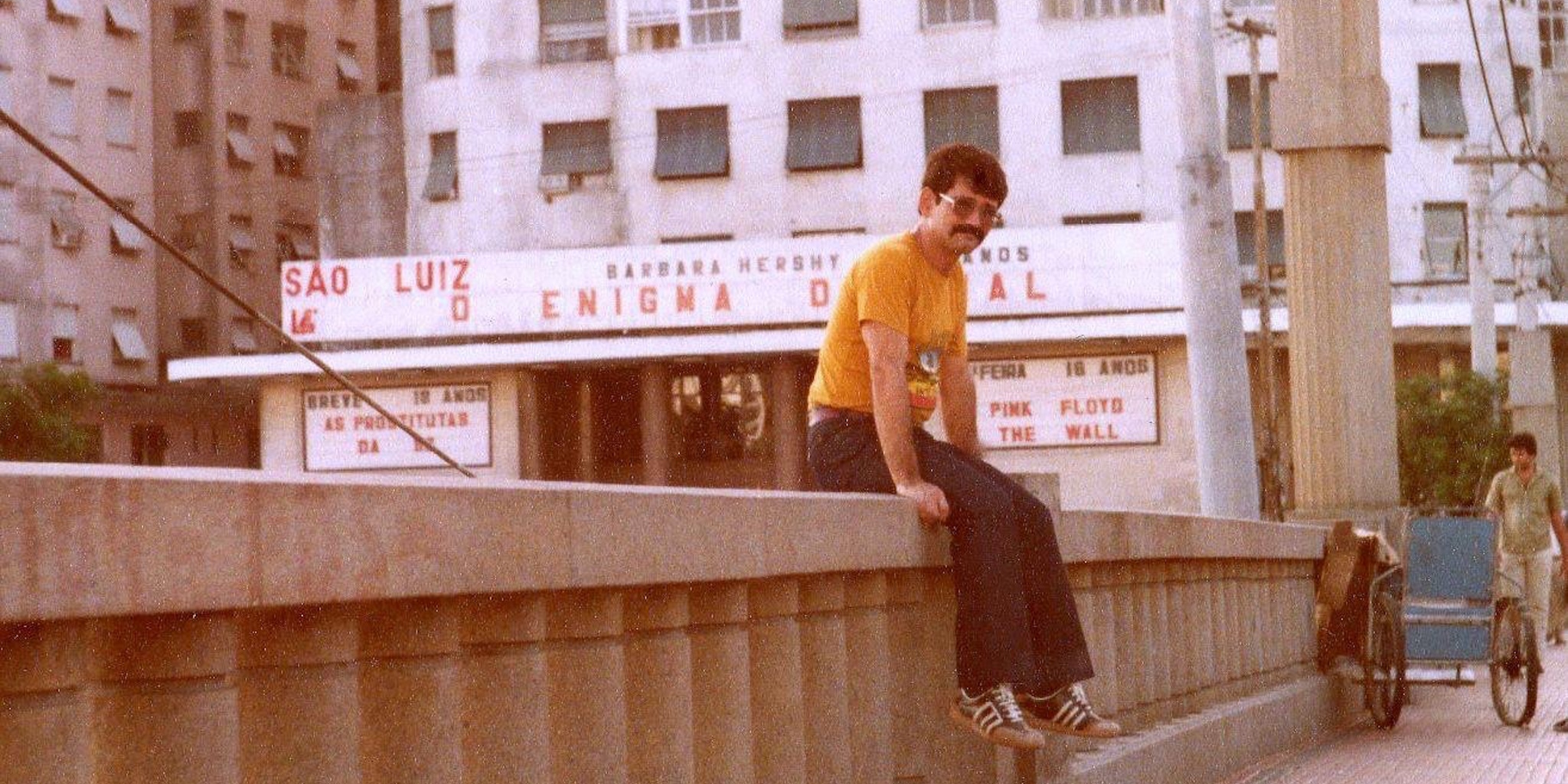

Much like a restless teenager venturing out into the neighborhood with his friends, Madonça’s documentary eventually leaves the old apartment to explore the history of downtown Recife’s legendary movie houses. Through archival news clippings, photographs, and film footage, Madonça leads the audience through the bustling nightlife of the area in the 1970s-90s, when seemingly every block had a theater screening Hollywood blockbusters (and other imports) to huge crowds. At one point, Madonça pulls out a hand-drawn street map of the area’s cinematic landmarks, illustrating that two rival movie houses once faced each other across the polluted Capibaribe River, like gunslingers dueling over box-office receipts. Another theater was originally a German state cinema, from a time when Brazil’s government was openly flirting with Nazism. (Madonça slides in some eyebrow-raising photos here of swastika-bedecked zeppelins hovering over World War II-era Recife.) After the war, such was the city’s economic and cultural power that American film studios maintained offices there, which led to a local boom in black-market movie memorabilia scavenged from their castoffs.

Nothing lasts forever, of course. As the economic hub of Recife shifted away from downtown, the nightlife dried up and the old cinemas began to close, the buildings converting into shopping malls and evangelical churches. By the time Madonça was a budding filmmaker in the 1990s, the writing was on the wall: One of his early projects involved profiling the old projectionist at one of his favorite movie houses, which was then preparing to shutter its doors forever. Anxiety about security in the neighborhood eventually led to high fences, window bars, and even razor wire on the homes surrounding the family apartment. Downtown was no longer a desirable place to live, or even to visit.

Madonça regards these changes with a subdued wistfulness, ultimately being less interested in articulating some grand thesis than in ruminating on the puzzle of time, place, and memory. In this, and in the collage-like quality of its moment-to-moment construction, Pictures of Ghosts bears a close resemblance to Terence Davies’ aching cinematic memoir, Of Time and the City (2008). For Madonça, downtown Recife has a distinct spirit, and although the area has been battered by shifting cultural and economic forces, he insists that the spirit remains. Yet the filmmaker’s unflagging affection for the Recife of his memory highlights the ship-of-Theseus enigma at the heart of his feature. Where does the essence of a place reside as it is replaced brick by brick? The director isn’t all that interested in explicitly answering this question, in light of his puzzling inclusion of a magical-realist coda that seems to crib from the Nick Cave documentary 20,000 Days on Earth (2014). However, like any good autobiographical film where the philosophical rustles just beneath the personal, Pictures of Ghosts suggests an answer: The soul of a place endures in those who remember it as it once was.

Pictures of Ghosts screens nightly at 7:30 p.m. on Mar. 15 – 17 at the Webster University Film Series.