“We’ve all felt that the body was empty of meaning,” asserts surgical performance artist Caprice (Léa Seydoux) in David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future (2022), “and we’ve wanted to confirm that, so that we could fill it with meaning.” This declaration kept oozing to mind during De Humani Corporis Fabrica, a documentary that tunnels deep into the inner space of our animal flesh with a searching fascination. The latest feature from anthropologist-filmmakers Luciena Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel (Leviathan, Caniba) is not seeking some hidden revelation as it zooms in on the membranous surface of a freshly birthed placenta or the malignant folds of an extracted breast tumor. As with all the films produced under the aegis of the Harvard University’s Sensory Ethnography Lab – where the co-directors have been working independently for 30 years and collaborating for the past decade – DHCF is a work of observation and invitation. It bids the viewer to gaze on the hidden vistas inside all of us and (perhaps) bestow them with meaning.

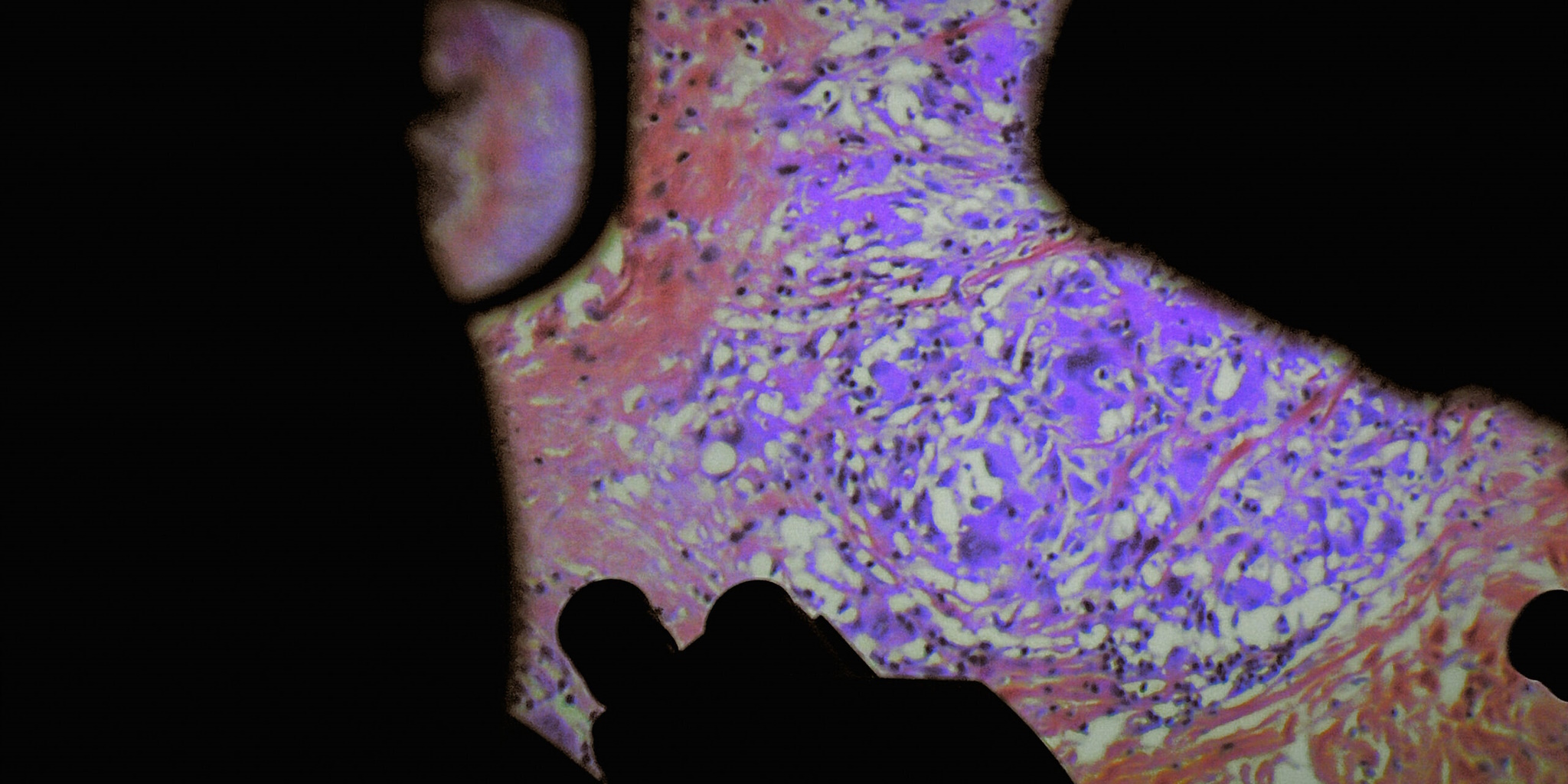

Seven years in the making, DHCF was filmed at several public hospitals in Paris with the consent and cooperation of patients, doctors, nurses, and administrators. (The filmmakers reportedly found it legally and logistically prohibitive to film in Boston, as originally planned, and eventually shifted their project’s focus to Paravel’s native France.) The footage that the directors garnered from their studies is roughly divisible into two categories. The first type consists of queasily up-close-and-personal scenes of various surgical procedures, including fixed-camera views of operating rooms and raw endoscopic footage captured from inside patients’ bodies. Viewers uncomfortable with such imagery should consider this a content warning: DHCF includes graphic footage of a spinal-fusion surgery, a caesarian-section birth, a cataract removal, a prostate surgery (including a sequence of a penis being catheterized), and various endoscopic views of unidentified tissues being poked, pulled, and sliced.

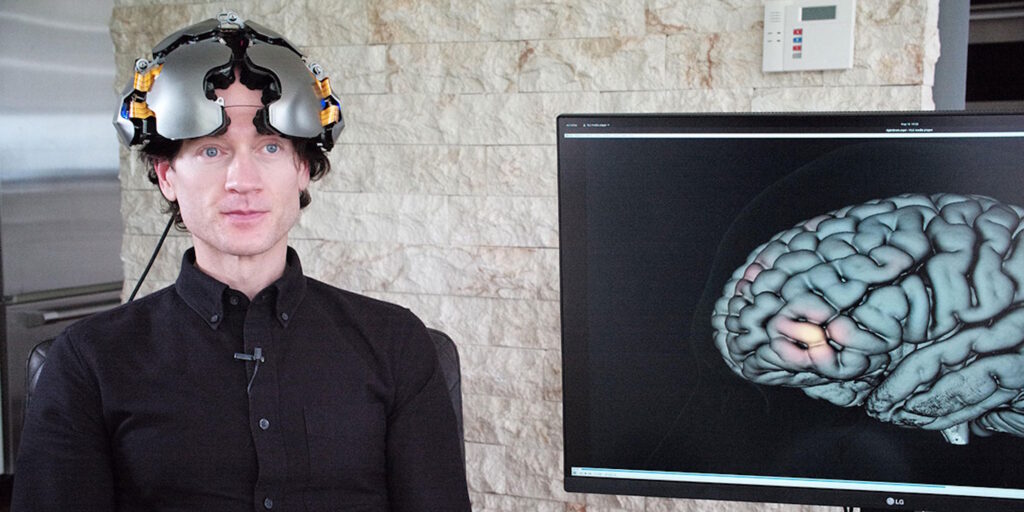

The second type of footage comprises verité sequences of everyday scenes in the hospitals’ various units. ICU nurses grouse justifiably about exhausting working conditions as they administer a sponge bath. Orderlies gently but firmly redirect a dementia-addled geriatric patient who has wandered away from their room. Mortuary workers listen to reggae as they dress a cadaver for its return to the deceased patient’s next of kin. Security guards prowl the endless passageways of chthonian sub-basements that seem to have been plucked straight out of Jacob’s Ladder (1990) or Session 9 (2001). Castaing-Taylor and Paravel employ a tiny “lipstick camera” for these workplace scenes, the device roughly mimicking the depth of field and angle of view in the more clinical, close-up footage. In this way, the filmmakers created a textural continuity across all their imagery, blurring the distinctions between the worlds without and within.

DHCF is just as intriguing aurally as it is visually. Workaday chatter floats above the white-noise hum of these massive medical-industrial complexes, providing glimpses of the hospitals’ internal culture. We overhear resentment over long hours, pity for hard-luck patients, superstitions about “bad rooms,” and irritation at sloppy laboratory practice. Most fascinating are the overhead conversations between the unseen doctors and nurses during the surgical procedures. Some are oddly soothing in their cafeteria-talk banality, such as a gripe session about rising rents in this or that Parisian neighborhood. More distressing are the surgeries that descend into methodological confusion and stressed-out bickering, as in the aforementioned prostate procedure. (“I’m a little lost here,” admits a surgeon at one alarming moment.) It feels a bit like one is listening to radio chatter during a deep-space foray to some alien world, and this viewer was often put in mind of the Mission Control and Lunar Module recordings that soundtrack Todd Douglas Miller’s documentary Apollo 11 (2019).

Any observational documentary set in a medical facility inevitably evokes the granddaddy of the subgenre, Frederick Wiseman’s Emmy-winning Hospital (1970). Although their film is hardly apolitical, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s approach is less interested in the nitty-gritty of process than in the philosophical potency of nose-on-the-glass sensation. As in Leviathan, their latest work immerses the viewer in a largely unfamiliar world and invites them to ruminate on the various ideas that intersect there, including those regarding the body, mortality, medicine, technology, and related political and economic institutions. This is not a film with a lucid thesis, but it does have quite a bit on its mind, and Castaing-Taylor and Paravel plainly find all these topics equally absorbing. The film’s air of anthropological fascination attains its fullest expression in the film’s bizarre coda. As New Order’s “Blue Monday” pulses on the soundtrack during an after-hours doctors’ party, the camera gawks at the pornographic frescoes in a hospital’s salle de garde – a raucous and defiantly problematic social space with a long tradition in French medical culture.

Early in the documentary’s development, the filmmakers toyed with structuring their material into seven “books,” in imitation of the 1543 anatomical treatise from which the film derives its name. Eventually this notion was abandoned in favor of a shaggier, more free-associative construction. Indeed, one criticism that can be levied against DHCP is that it feels a little too shapeless, so averse to making any kind of definitive statement that it can stray into aimless impressionism. On the positive side, however, this looser approach allows the feature’s poeticism to emerge more organically. The viewer’s mind might connect the squalling from a still-sticky newborn infant to the distressing yelps from a nonverbal elderly patient, for example, but it’s not the sort of parallel that the filmmakers insist on. Similarly, given the resemblance between the macrocosm of a hospital’s labyrinthine corridors and the microcosm of a vascular system, one might start to wonder if this recurring, dendritic form has some primordial significance for our species. Or maybe it’s just a coincidence, one of the pattern-seeking lies that we pour into the empty vessel of our imperfect flesh.

De Humani Corporis Fabrica screens nightly at 7:30 p.m. on May 19 – 21 at the Webster University Film Series.