[Originally published at Cinema St. Louis’ The Lens.]

Look: It’s difficult for anyone to keep up these days. The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, under immense pressure from their ABC overlords and others, is scrambling hard to stay relevant under a public microscope. However, it’s even harder to feel sympathetic for them; it’s not like they don’t deserve the heat. #OscarsSoWhite exposed the institution as old, male, and White, which has been true for nearly a century now. After internal regime changes, diversity initiatives, eligibility-requirement updates, and more, maybe the times are finally a-changin’?

However, in their recent grasps for relevancy, there have been steps forward and back: for every Parasite, there’s a Green Book. The ceremony itself, hemorrhaging millions of viewers for years, now does the same. For every Soderbergh-directed no-frills, no-host affair, there’s an all-frills, three-host #OscarsCheersMoment-saluting ceremony sans eight awards categories.

For those of us who follow along, the whiplash is expected by now, and yet every year we still take the journey to that final moment when that last golden boy is handed to the producers of the Best Picture of the year (or to the wrong ones … or to no one …). Perhaps unsurprisingly and due to the remarkable year in film that was 2021, the category’s nominees for the 2022 ceremony provide a remarkably steady ride, even though the breadth of quality is greater than last year’s lineup. Adam McKay looks up from the bottom (once again), but the average is kept high by a few genuinely great films by great filmmakers and one stone-cold masterpiece cruising its way across the finish line.

10. Don’t Look Up

Don’t Look Up or: How Adam McKay Learned the Wrong Lessons From Dr. Strangelove and Went on Twitter to Yell at Everyone to Love His Bomb. Netflix gave Chicken Little a platform – and an unwieldy, mis-wielded starry cast – to tell us that the sky is falling as we’re all already wading through the debris. I can doomscroll for 2.5 hours on my own, thank you very much.

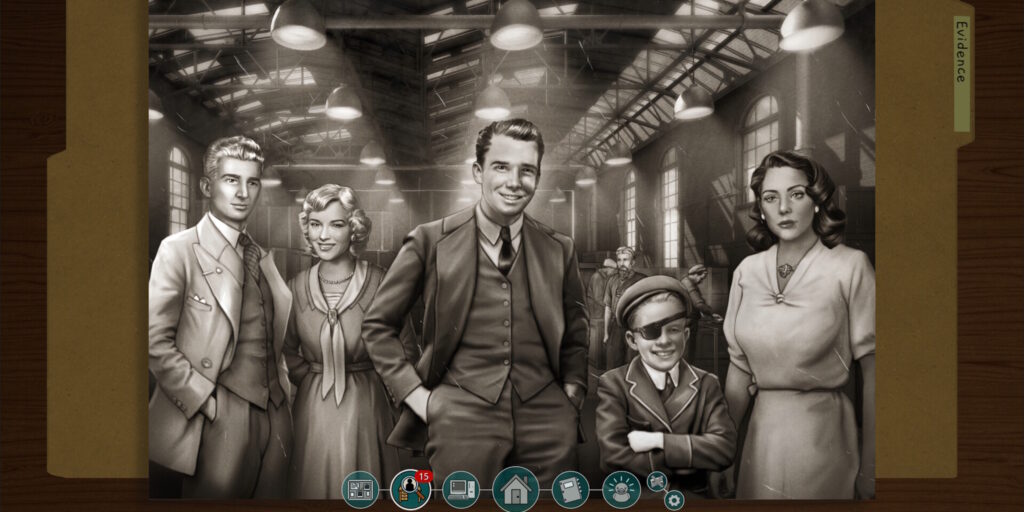

9. Nightmare Alley

Guillermo del Toro’s soulless remake of Edmund Goulding’s 1947 carnival noir (or a second adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel) was seemingly pushed into the nominee list by the “craft” departments. Its three other nominations – Production Design, Cinematography, and Costume Design – speak volumes as to del Toro’s strengths in design but also his increasingly slack helming. Only the game Cate Blanchett’s femme fatale Freud is able to breathe in the director’s overly gilded iron lung, and by the time he gets to the punchline nearly 2.5 hours later, he’s demonstrated he’s all theoretical bark and no bite – except for the poor geek’s daily chicken.

8. Belfast

From the marketing jump, multi-hyphenate Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast has been tagged as his Roma: the Irishman’s own mid-20th-century-set semi-political memoir. It’s an appropriate comparison, except his black-and-white memory palace is more Hallmark Channel than Criterion Channel. Emotions are stirred, tears are jerked, heartstrings are pulled, and all with an obvious deliberateness that’s mostly innocuous and ultimately forgettable.

7. Dune

Maybe there’s a quality to Frank Herbert’s Dune novels that, in context, makes what seems like their silliest attributes credible. Removed from those pages, it’s Minnesota Joe sucking up space dust that allows him to ride giant sandworms while controlling Fremen (free men, get it?) with his mind-voice. (I don’t know what they’re up to, but I have no choice but to stan those goth-dragged queens, the Bene Gesserit sisters). Maybe I’ll pick one of those books up one day and understand exactly what’s going on in any film adaptation of Dune. (Spoiler: I won’t.) At the very least, from this infamously “unadaptable” source, David Lynch made a wonky, wondrously mucky camp object supreme, and now the self-serious Denis Villeneuve has made one (-half?) of his more pleasurable (if still lumbering at – checks notes – 2.5 hours) films yet.

6. King Richard

After a few failed attempts at nabbing the Big One (with some close calls like Ali and The Pursuit of Happyness and some big misses like Seven Pounds and Collateral Beauty), Will Smith finally found his game-set-match in Richard Williams, the father-manager of tennis titans Venus and Serena Williams. In some ways, King Richard is better than an attempted flat serve for Oscar glory: Director Reinaldo Marcus Green and writer Zach Baylin give due space to the female Williams family members, with Supporting Actress nominee Aunjanue Ellis as the matriarch. Elsewhere, the obfuscation of reality – the real-life Williams family members are producers – for more traditional Hollywood beats is painfully obvious (including, you guessed it, its 2.5 hour runtime).

5. CODA

CODA shares a similar saccharine sweetness with Belfast, but at least it comes with a balancing sourness. Siân Heder deftly navigates the intersections of economic disparity, ability issues, and the American family unit while also slavishly adhering to rote finding-your-voice narrative conventions. Like Ruby (Emilia Jones), the musically inclined teenage daughter of deaf parents (Marlee Matlin and future Supporting Actor winner Troy Kotsur), the writer-director has a lot of plates spinning, and she just barely pulls off keeping them in the air.

4. The Power of the Dog

A piece of silk and about an hour’s runtime reveal Jane Campion’s interest in adapting Thomas Savage’s 1961 cult Western novel. Repression of desire can erupt in many ways, not just in the explicit collision of bodies the master filmmaker of The Piano and In the Cut often displays. Sometimes it’s a small gesture of emotional intimacy between newlyweds. Sometimes it’s a slow flow of rage leading to a surgically precise act of vengeance. By the time these active cores are exposed, it’s clear that it could only be the uncommonly empathetic Campion to do so.

3. West Side Story

The great nostalgist Steven Spielberg – with help from screenwriter Tony Kushner, a great anti-nostalgist – took a wrecking ball to Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins’ original 1961 adaptation of Broadway all-timer West Side Story. It’s not a complete rebuild; a major problem is its narrative fidelity to the source, resulting in some slight lulls in its 2.5-hour runtime (runtime think piece forthcoming, I guess). However, Spielberg’s furious display of virtuosic filmmaking, along with Kushner’s nudging of class and race issues in the correct direction, make for one of the most palpably thrilling justifications for the continued relevance of the flailing Dream Factory.

2. Licorice Pizza

Paul Thomas Anderson’s day-in-the-life mosaic Magnolia has always been referred to as his great Robert Altman homage. That’s a surface-level reading of both Magnolia and Altman – they’re not just all sprawl and connection. Licorice Pizza arrives fresh out of the oven bubbling with the real rich Altman ingredients: wry observation of irrational human behavior, the ribald comedy naturally springing from it, and free-wheeling portraiture of the seemingly mismatched pieces that make up a whole pie. Anderson has always situated his films in the space where opposite charges attract, but here he’s left so much breezy room that some have chosen to walk away filling it instead of allowing it to electrify them.

1. Drive My Car

“If we hope to truly see another person, we have to start by looking within ourselves.” This line from Haruki Murakami’s “Drive My Car” within his anthology Men Without Women finds its way into nascent master Ryūsuke Hamaguchi’s adaptation of the short story. It may feel like a platitude removed from context, but the supreme dramatist complicates his inherited thesis by testing the limits of intimacy in myriad ways. What do we give of ourselves when we tell our stories? Who gets to own those pieces once we do so? Can we ever control what they do with them? At what point do these stories fail in letting someone else truly see us? The organic, grassroots ascendancy of the slow-burn (justified) three-hour Japanese melodrama about a theater production into the upper ranks of the Academy’s favorite films of the year will likely puzzle awards pundits for some time. To see exactly how it pulled off this trick, all one has to do is hop in the passenger seat for Hamaguchi’s epic exploration of the essentials of human experience.